Articles J to Z

- Details

- Category: Articles J to Z

The War Memorials of Stornoway , Lewis and Tarbert , Harris. Outer Hebrides

by Eric Hunter

World War I has left an indelible mark on these islands. The population of Lewis prior to WW1 was roughly 30 000, of those nearly 7000 men joined up.1,151 died during the conflict 17% In terms of percentages. Lewis had lost twice as may men as other parts of Britain

To amplify the loss to the community , the wrecking of the troop ship Iolaire on 1st January 1919 bringing home demobbed sailors compounded the communities grief.

Subsequently, although hostilities for the First World War ended on 11 November 1918, the war is held to have ended in 1919 in Lewis and Harris because of a large loss of life right at the start of that year.

The Stornoway War Memorial dominates the town. Situated on 300 foot hill known as Cnoc nan Uan it stands imperious a constant reminder to this communities loss. Made of local stone it stands 84 feet tall and resembles a Scottish Castle. Visitors were able to climb the stairs inside the tower to four chambers which represented the parishes of the island. Brass plaques commemorating all the dead of the lined the walls of the chambers. Unfortunately the ravages of the Hebridean weather have taken their toll and it is unsafe now to climb the tower. 22 large rocks making an uncomplete circle now stand guard at the base of the tower. Each stone has the names of the fallen from both World Wars.

The memorial is impressive and still seems to have an aura of the grief felt by this tight knitted community.

The War Memorial at Tarbert , the main town of Harris is designed on similar lines in that

The names on the list are ordered by the village from which the men last departed the island. There is no complete list of casualties, originating from the Isle of Harris. Many lived away from the island by the time they joined up, whether it be elsewhere in the United Kingdom or overseas. Any reference to these men would have pointed to their last residence, with no obvious link to the island.

The memorial stands in a dominant position at the junction of the High Street and the road leading to the Harbour.

- Details

- Category: Articles J to Z

Earl Haig and his wife, Dorothy Maud, lie side by side in a truly wonderful setting within the ruins of Dryburgh Abbey in the Scottish Borders. The other famous burial at the Abbey is Sir Walter Scott, who is laid to rest in a large marble sarcophagus; the contrast between these graves is remarkable.

The Haigs’ stones are of the style used by the CWGC. Inscribed is the name Douglas Haig, with no military rank or acknowledgement of his Earldom. Both birthdates and date of death are recorded, and no other postscripts or sentiments. The Queens Hussars emblem, Haig’s first regiment, is engraved above his name. Dorothy’s stone maintains the frugal narrative and states simply “His wife”.

On the rear side of Douglas Haig’s stone are the emblems of the regiments he was Colonel in Chief of, 17/21st Lancers, Royal Horse Guard, The London Scottish and the Kings Own Scottish Borders. Behind the headstones away from the graves is a Cross of Sacrifice, erected by the cavalry regiments he was Colonel in Chief of. Poignantly, the inscription on the Cross reminds all of Haig’s revered role in the Great War and the esteem held by the troops who served under him –

“This Cross of Sacrifice is identical with those which stand above the dead of Lord Haig’s armies in France and Flanders”

Haig was given a State funeral and a lying in state in Edinburgh before his interment. Heads of state and royalty paid their respects . The visit to see Field Marshall Haig’s resting place in its idyllic setting makes me suspect he would not have liked the fuss and, being a religious man, settled for piety once he met his maker.

- Details

- Category: Articles J to Z

Great War memorials from around the world

Eric Hunter

With the lifting of travel restrictions following the pandemic our members and fellow Great War enthusiasts are again traveling abroad. The war was truly worldwide and remembered by many memorials in numerous countries.

Terry Jackson was on his travels and he was in Kingston, Ontario and has sent a picture of the very impressive Byng Arch. Terry writes:

On 25 June 1923, as part of that year's Graduation Day activities the Governor-General of Canada, His Excellency Viscount Byng, of Vimy, officially laid the cornerstone of the Memorial Arch. Within the stone in a sealed copper box, were nominal rolls of Cadets and Staff, pamphlets concerning the Arch, the RMC Review of May 1923, Canadian coins and stamps and the Roll of Honour of the College. Designed by architect John M. Lyle, Esq., of Toronto and funded by the Royal Military College Club of Canada with monies raised from ex-cadets and other friends of the College.

The Arch was unveiled on June 15, 1924, by Mrs. Joshua Wright, mother of cadet 558 Major G.B. Wright, DSO, RCE, and 814 Major J.S. Wright, who gave their lives in the First World War. The details of the ceremony are engraved on the cornerstone.

The Memorial Arch stood completed in 1924 and commemorates the ex-cadets who had lost their lives in the Great War and earlier conflicts. The stones around the Arch continue to bear the names of cadets from the college that have fallen in conflict, in peacekeeping or other causes while in service. It is 46 feet high and 42 feet wide and is constructed of granite and Indiana limestone. On the back and front pedestals are low reliefs, exquisitely carved, of ancient armorial designs. The cost of the structure was about seventy thousand dollars.

The Arch was dedicated to the memory of all “the Ex-Cadets of the Royal Military College of Canada Who Gave Their Lives for the Empire.” The names begin with No. 52 Captain WG Stairs who died during the Emir Pasha Relief Expedition 1887 – 1890; followed by No. 62 Captain WH Robinson who died in West Africa 1892. There are then five names of Ex Cadets who were killed during the Boer War 1899 – 1901, followed by those from 1914 – 1918.

On September 25, 1949 two granite pylons, one on each side of the Arch, were unveiled by the Governor General, Viscount Alexander of Tunis, on which are recorded the names of those Ex Cadets who gave their lives between 1926 and 1945. In 2006 another plaque, donated by former Commandants, was attached to the East pylon. On it the names of Ex Cadets who have died on active service since 1945 are recorded.

Malcom Jackson sends a photograph of the War Memorial overlooking the harbour in Hobart, Tasmania. The pines that surround it have come from Gallipoli.

Gerry Bhim has sent in a photograph from Port Louis in Mauritius. The islands history is shared with the French who also colonised the island at one time. Many residents held a deep affection to France and when war broke out many enlisted in the French Army. Subsequently the memorial shows both a British Tommy and a French Poilu.

Eric Hunter sent this picture from Funchal, Madeira. It is often forgotten that Portugal was one of Britain’s main allies in the Great War sending troops not just to the Western front but also to East Africa.

- Details

- Category: Articles J to Z

The Woodford Cross

Eric Hunter

In the graveyard of Christ Church, Woodford nr Stockport there lies a large ornate wooden cross, rotten with age, broken, it is placed over its original footing. Upon the cross the epitaph reads:

“In Loving memory to Sec’ Lieut Frank S. Brooks. 20 Manchester Reg (Pals)

Killed in Action at Fricourt France. July 1st 1916.

For King and Country”.

Frank Brooks was born in 1897. His father Arthur was a successful solicitor with offices in Manchester and Stockport. The family lived in Gately, Stockport when Frank enrolled at Manchester University to read Law with an ambition to be involved eventually within his father’s business. Frank prior to completing his studies enlisted in the Special Reserve and became a Private in the North Staffordshire Regiment. He was mobilised at the outbreak of war but in November 1914 he applied for a Commission and was posted to 20th Manchester (5th Pals).

On the First of July 1916 the 5th Manchester’s attacked at 14.30 on a front opposite Bois Francais. The dividing front lines were a short distance 80 – 220 yards. The attack was brief and by 14.45 the German front trench was taken. Frank, his Commanding Officer and over 300 of the regiment fallen, were injured or missing. The successful attack by the Manchester’s at Fricourt meant that the bodies of the fallen could be buried and recorded in a dignified manner. Lieutenant Brooks and his comrades were laid to rest in the captured German trench.

At some point during or after the war, the family moved to nearby Bramhall Moor Lane and the Woodford church presumably became their place of worship. Frank is not buried in Woodford, neither is his name included on the War memorial within the church. After the war Frank’s body was exhumed from the war burial and interred in Danzig Valley British War Cemetery. The family had this memorial made and erected in their local church as an act of very personal remembrance. Further down the cross there is another inscription:

“also of Cyril, infant child of Edith and Arthur Brooks.”

This was a very personal act of remembrance, one which was probably evoked each week as they worshiped. Their loss was not just their sons but it appeared their future.

My initial feelings when I first discovered this rotten fallen cross was, as a Great War enthusiast, a memorial in a tragic state of repair. When I reflect however I begin to appreciate that memorials have multiple significances. If the Brookes had wanted a memorial to last forever they would have commissioned it from stone not wood. It was a personal statement for lives lost which they had no control over.

I have not researched if there are still members of the Brooks family that live locally and keep Frank and Cyril’s memory alive. We in the WFA do remember but not in the emotional context as to which this memorial was erected. To that end is intervening and restoring or replacing the cross an appropriate response, or should we acknowledge and note its existence and let time ultimately reduce any personal attachment?

- Details

- Category: Articles J to Z

The Inventor of Dazzle Camouflage

Terry Jackson

Norman Wilkinson CBE RI (24 November 1878 – 30 May 1971) was a British artist who usually worked in oils, water colours and drypoint. He was primarily a marine painter, but also an illustrator, poster artist, and wartime camoufleur. Wilkinson invented dazzle painting to protect merchant shipping during WW1. He was born in Cambridge, England and attended Berkhamsted School, Hertfordshire and at St. Paul's Cathedral Choir School in London. His early artistic training occurred in the vicinity of Portsmouth and Cornwall, and at Southsea School of Art, where he was later a teacher. He also studied with seascape painter Louis Grier. While aged 21, he studied academic figure painting in Paris,

Wilkinson's career in illustration began in 1898, when his work was first accepted by The Illustrated London News, for which he then continued to work for many years, as well as for the Illustrated Mail. Throughout his life, he was a prolific poster artist, designing for the London and North Western Railway, the Southern Railway and the London Midland and Scottish Railway. It was mostly owing to his fascination with the sea that he travelled extensively to such locations as Spain, Germany, Italy, Malta, Greece, Aden, the Bahamas, the United States, Canada and Brazil. He also competed in the art competitions at the 1928 and 1948 Summer Olympics.

During the First World War, while serving in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, he was assigned to submarine patrols in the Dardanelles, Gallipoli and Gibraltar, and, beginning in 1917, to a minesweeping operation at HMNB Devonport.

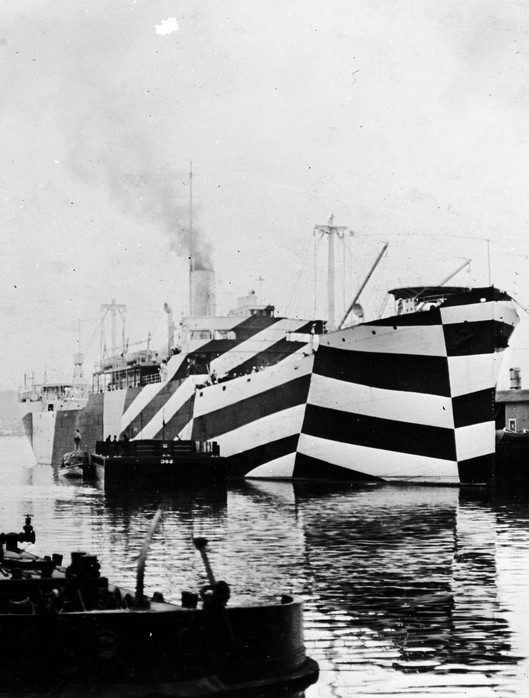

In April 1917, German U-boats achieved unprecedented success in torpedo attacks on British ships, sinking nearly eight per day. Wilkinson arrived at what he thought would be a way to respond to the submarine threat. He decided that it was all but impossible to hide a ship on the ocean (if nothing else, the smoke from its smokestacks would give it away). Thus, he thought how could it make it difficult to aim at a ship through a periscope? He decided that a ship should be painted "not for low visibility, but in such a way as to break up her form and thus confuse a submarine officer as to the course on which she was heading”.

Norman Wilkinson with a model ship

After initial testing, Wilkinson's plan was adopted by the British Admiralty, and he was placed in charge of a naval camouflage unit, housed in basement studios at the Royal Academy of Arts. There, he and about two dozen associate artists and art students (camoufleurs, model makers, and construction plan preparators) devised dazzle camouflage schemes, applied them to miniature models, tested the models (using experienced sea observers), and prepared construction diagrams. These were used by other artists at the docks (one of whom was Vorticist artist Edward Wadsworth) in painting the actual ships. Wilkinson was assigned to Washington DC for a month in early 1918, where he served as a consultant to the U.S. Navy, in connection with its establishment of a comparable unit (headed by Harold Van Buskirk, Everett Warner, and Loyd A. Jones).

After the war, there was some contention from other artists about who had originated dazzle painting. However, at the end of a legal procedure, Wilkinson was formally declared the inventor of dazzle camouflage, and awarded monetary compensation.

Dazzle camouflage on a real ship

Dazzle camouflage on a real ship

Second World War camouflage

During the Second World War, Wilkinson was again assigned to camouflage, not in dazzle-painting ships which had fallen out of favour, but with the British Air Ministry where his primary responsibility was the concealment of airfields. He also travelled extensively to sketch and record the work of the Royal Navy, the Merchant Navy and Coastal Command throughout the war. An exhibition of fifty two of the resulting paintings, The War at Sea, was shown at the National Gallery in September 1944. It included nine paintings of the D-Day landings, which Wilkinson had witnessed from HMS Jervis, plus naval actions such as the sinking of the Bismarck. The exhibition toured Australia and New Zealand in 1945 and 1946. The War Artists' Advisory Committee bought one painting from Wilkinson. He donated the other 51 paintings to the Committee.

Wilkinson was elected to the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours (RI) in 1906, and became its President in 1936, an office he held until 1963. He was elected Honourable Marine Painter to the Royal Yacht Squadron in 1919. He was a member of the Royal Society of British Artists, the Royal Institute of Oil Painters, the Royal Society of Marine Artists, and the Royal Scottish Society of Painters in Watercolour. He was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 1918 New Year Honours, and a Commander of the Order (CBE) in the 1948 Birthday Honours.