Terry Jackson

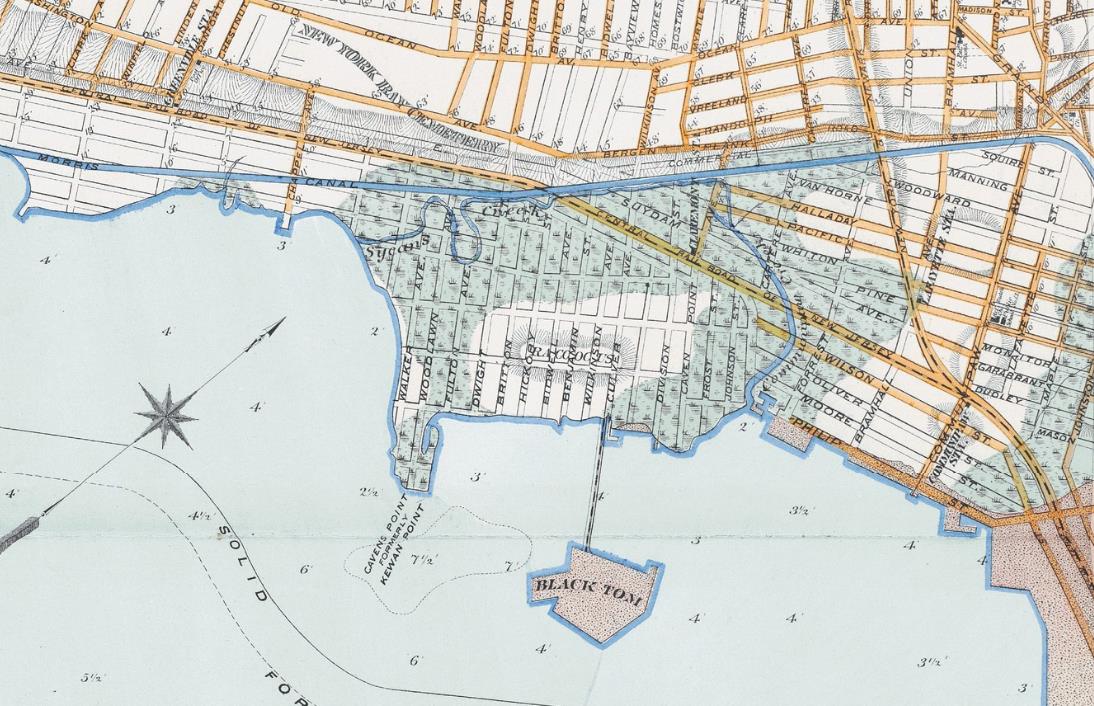

‘Black Tom’ originally referred to an island in New York Harbour next to Liberty Island. The island was artificial, created by land fill around a rock of the same name, which had been a local hazard to navigation. By 1880, the island was transformed into a 25 acre promontory with a causeway and railroad built to connect it with the mainland and was used as a shipping depot. Between 1905 and 1916, the Lehigh Valley Railroad, which owned the island and causeway, expanded the island with land fill and the entire area was annexed by Jersey City. A mile-long pier on the island housed a depot and warehouses for the National Dock and Storage Company.

Franz von Rintelen

Black Tom was a major munitions depot for the North Eastern United States. Until early 1915, U.S. munitions companies could sell to any buyer. After the Blockade of Germany by the Royal Navy, however, only the Allied powers could purchase from them. As a result, Imperial Germany sent secret agents to the United States to obstruct the production and delivery of war munitions that were intended to be used by its enemies.

On the night of the attack, about 2,000,000 lbs of small arms and artillery ammunition were stored at the depot in freight cars and on barges, including 100,000 lbs of TNT on Johnson Barge No. 17. All were waiting to be shipped to Russia. Jersey City's Commissioner of Public Safety, Frank Hague, later said he had been told the barge was "tied up at Black Tom to avoid a twenty-five dollar charge”.

Just after midnight on 30th July 1916, a series of small fires were discovered on the pier. Some guards fled, fearing an explosion. Others attempted to fight the fires and eventually called the Jersey City Fire Department. At 2:08 am, the first and larger of the explosions took place, the second and smaller explosion occurring around 2:40 am. A notable location for the first major explosion was around the Johnson Barge No. 17. The explosion created a detonation wave that travelled at 24,000 feet per second with enough force to lift firefighters out of their boots and into the air. Fragments from the explosion spread out over long distances. Some lodged in the Statue of Liberty and some in the clock tower of the Jersey Journal building in Journal Square, over a mile away, stopping the clock at 2:12 am.

The explosion was the equivalent of an earthquake measuring between 5.0 and 5.5 on the Richter scale and was felt as far as Philadelphia (100 miles). Windows were broken as far as 25 miles away, including thousands in Lower Manhattan. Some window panes in Times Square were shattered. The stained glass windows in St. Patrick's Church were destroyed. The outer wall of Jersey City's City Hall was cracked and the Brooklyn Bridge was shaken. People as far away as Maryland (2800 miles) were awakened by what they thought was an earthquake.

Property damage from the attack was estimated at $20,000,000 (equivalent to $470,000,000 now). On the island, the explosion destroyed more than one hundred railroad cars, thirteen warehouses, and left a 375 feet-by-175 feet crater at the source of the explosion. The damage to the Statue of Liberty was estimated to be $100,000 ($2,350,000 now) and included damage to the skirt and torch.

Immigrants being processed at Ellis Island had to be evacuated to Lower Manhattan. Although one contemporary newspaper report estimated that up to seven people died in the attack, four did definitely die- a Jersey City policeman, a Lehigh Valley Railroad chief of police, a ten-week-old infant, and the barge captain.

In the immediate aftermath of the explosion, two watchmen who had lit smudge pots to keep away mosquitoes were questioned by police but the police soon determined that the smudge pots had not caused the fire and that the blast had likely been an accident.

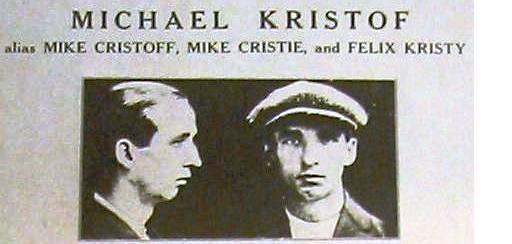

Soon after the explosion, suspicion fell upon Michael Kristoff, a Slovak immigrant. Kristoff who would later serve in the United States Army in World War 2, admitted to working for German agents transporting suitcases in 1915 and 1916 while the US was still neutral. According to Kristoff, two of the guards at Black Tom were German agents. It is likely that the bombing involved some of the techniques developed by German agents working for German Ambassador Count Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff and German Naval Intelligence Officer Franz von Rintelen, using the cigar bombs developed by Dr. Walter Scheele.

Von Rintelen used many resources at his disposal, including a large amount of money. Von Rintelen used this money to make generous cash bribes, one of which was notably given to Kristoff in exchange for access to the pier. Suspicion at the time fell solely on German saboteurs such as Kurt Jahnke and his assistant Lothar Witzke, who are still judged as legally responsible. It is also believed that Kristoff was responsible for planting and initiating the incendiary devices that led to the explosions. Later investigations in the aftermath of the Annie Larsen affair in 1915 (a gun running ship) unearthed links between the Ghadar Indians conspiracy who were expatriates and the Black Tom explosion.

Von Rintelen used many resources at his disposal, including a large amount of money. Von Rintelen used this money to make generous cash bribes, one of which was notably given to Kristoff in exchange for access to the pier. Suspicion at the time fell solely on German saboteurs such as Kurt Jahnke and his assistant Lothar Witzke, who are still judged as legally responsible. It is also believed that Kristoff was responsible for planting and initiating the incendiary devices that led to the explosions. Later investigations in the aftermath of the Annie Larsen affair in 1915 (a gun running ship) unearthed links between the Ghadar Indians conspiracy who were expatriates and the Black Tom explosion.

Additional investigations by the Directorate of Naval Intelligence also found links to some members of the Irish Clan na Gael group and Communist elements. The Irish socialist James Larkin asserted that he had not participated in active sabotage, but had encouraged work slow-downs and strikes for higher wages and better conditions in an affidavit to the lawyer John Jay McCloy in1934 when McCloy was an legal advisor to the US government. There was not an established national intelligence service at the time of the explosion, other than diplomats and few military and naval attaches, making the investigation difficult. Without a formal intelligence service at the national level, the United States only had rudimentary communications security and no federal statute forbidding peacetime espionage or sabotage. This made the connections to the saboteurs and accomplices almost impossible to track.

This attack was one of many during the German sabotage campaign against the Un

The Russian government sued the Lehigh Valley Railroad Company operating the Black Tom Terminal on grounds that due to lax security there was no entrance gate and the territory was unlit which permitted the loss of their ammunition. They argued that due to the failure to deliver them the manufacturer was obliged by the contract to replace them.

The Lehigh Valley Railroad, advised by the then lawyer McCloy sought damages against Germany under the Treaty of Berlin from the German-American Mixed Claims Commission. The Mixed Claims Commission declared in 1939 that Imperial Germany had been responsible and awarded $50 million (the largest claim among others) in damages which Nazi Germany refused to pay. The issue was finally settled in 1953 at $95 million (interest included) with the Federal Republic of Germany. The final payment was made in 1979.

The Black Tom explosion resulted in the establishment of domestic intelligence agencies for the United States. The Police Commissioner of New York, Arthur Woods, argued, "The lessons to America are clear as day. We must not again be caught napping with no adequate national intelligence organization. The several federal bureaus should be welded into one and that one should be eternally and comprehensively vigilant."

The Black Tom explosion resulted in the establishment of domestic intelligence agencies for the United States. The Police Commissioner of New York, Arthur Woods, argued, "The lessons to America are clear as day. We must not again be caught napping with no adequate national intelligence organization. The several federal bureaus should be welded into one and that one should be eternally and comprehensively vigilant."

The explosion also played a role in how future presidents responded to military conflict. President Franklin D. Roosevelt used the Black Tom explosion as part of his rationale for the internment of Japanese-Americans following the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941.

The incident also influenced public safety legislation. As a result of the sabotage techniques used by Germany and the United States' declaration of war on Germany, it led to the creation of the Espionage Act passed by Congress in late 1917. Landfill projects later made Black Tom Island part of the mainland, and it was incorporated into Liberty State Park.