Chairman’s comments

Strange Times Continue!

In normal circumstances our last meeting would have been on 8th May which coincided with the 75th anniversary of VE Day. On TV we have seen a lot of good documentary reflecting the hardships borne by our forces overseas but also by those civilians on the home front during the WW2. Looking back at our forebears in 1945 and their celebrations we’re reminded of their happiness at the end of the long struggle they had experienced during those wartime years.

Our meeting was cancelled of course and whilst our marvellous NHS continue to look after all those stricken with the Covid19, and various organisations research to find a possible vaccine, we are all staying at home to support the government’s self-distancing policy.

We can only hope that things will have changed for the better by end July but we currently have no way of knowing. We had our star speaker John Derry booked in August but sadly this has also been cancelled.

To keep our Branch in-touch with you all I arranged with the May speaker, to submit an article for the emailed edition of ‘Up the Line’. Mike Hally is in the final year of his PhD at the University of Edinburgh. He has for many years been an independent radio producer, making programmes for the BBC, including historical documentaries about aspects of Remembrance for Radio 4. His article ‘Peace Day’ is based on his proposed talk.

Terry Jackson has kindly volunteered to provide an article for each edition during our shutdown. I will also find additional special articles for your interest.

I again recommend you look at the WFA website and I can particularly recommend the WFA YouTube section for video presentations by numerous historians speaking at WFA events and the Podcasts of which 140+ have been produced and made available by Dr Tom Thorpe, WFA Trustee.

Although the centenary years of the 1914/1918 conflict have passed, we will continue to be interested in this war that altered the futures of so many people and families. Many aspects will continue to be discussed for a long time to come. Our monthly meetings will re-commence when possible.

Ralph Lomas

Terry is hard at work!

We have four new articles by Terry on the website. He has been focussing on the neutrals and their role in WWI. The articles are:

The Netherlands in WWI - click here

PoWs and the QVJFA - click here

Swiss Red Cross and PoWs -click here

Switzerland in WWI - click here

Peace Day 19 July 1919

As uncertainty and unrest followed the Armistice to the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June 1919.

Peace Day, comprised a military procession that wound its way for seven miles through central London, crossing and re-crossing the Thames, along with a variety of festivities in Hyde Park, and numerous other events around the country.

The most memorable image of the day was the sight of military and naval men and women, of all ranks and many countries, saluting the newly-built, temporary, Cenotaph, which symbolised the dead. Yet the details of the day’s events, even the date itself, were in doubt until just a few weeks beforehand. This reflected the uncertainty and unrest that characterised the period from the Armistice on 11 November 1918 to the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June 1919.

The Armistice was initially for just one month, and renewed in December for another month. At the beginning of January, soldiers’ strikes spread across the UK and northern France; they were fed up with the slow pace of demobilisation and doing drills, church parades, route marches and the like when, they felt, the war was over. Yet the Paris Peace Conference didn’t even begin until 18 January, by which time the Armistice had been renewed again. By the time that in turn expired, in mid-February, the extent of the task of negotiating peace had become clear, and this time the renewal was for a whole year.

It was not only serving soldiers who were restless. Three major ex-service organisations, the National Association of Discharged Sailors and Soldiers, the National Federation of Discharged and Demobilised Sailors and Soldiers, and the Comrades of the Great War had formed in 1917, the first two from very radical roots, the third a more conservative counterweight. By 1919 they were competing for new members among the discharged veterans flooding home, and pressuring the Government to improve war pensions and dependants’ allowances, re-train the disabled, create jobs, and much more. In March, the Federation published a remarkable ‘General Programme’ for the country, encompassing an end to secret treaties, abolition of the House of Lords, universal adult suffrage for men and women, a welfare system to ‘banish destitution and want from the cradle to the grave’, equal pay for women, and a great deal more. Rowdy demonstrations by ex-service men and women were frequent, most dramatically on 26 May, when a meeting in Hyde Park became heated and the veterans marched to Westminster, where they clashed with a police cordon, violently enough to alarm MPs inside Parliament.

By this time, a committee of the War Cabinet was planning how to mark the signing of a peace treaty, although nobody knew when that might happen. It was chaired by Lord Curzon, famous for his love of creating vast, spectacular, and meticulously organised ceremonies. His committee included the Home Secretary, First Commissioner of Works, and representatives of the Admiralty, War Office and Colonial Office, though no-one from an ex-service organisation. There wasn’t much to discuss, as progress in Paris was slow, so their first report, on 23 April, just recommended that any treaty should be marked by a military demonstration on a Saturday, and thanksgiving services on the Sunday.

A few weeks later their plans expanded to four days of celebrations in the first week of August, including Saturday, Sunday and the Bank Holiday, in order to cause ‘as little dislocation as possible to the industrial life of the country’. Curzon also told the Cabinet, rather ominously, that the decision to ‘fix the celebrations for so far ahead as August’ was ‘in case anything untoward should happen … considering the disturbed state of Europe and the world at the present moment.’

Finally, on 28 June 1919, the Treaty of Versailles was signed, and the War Cabinet met two days later to discuss ‘Peace Celebrations’. Curzon reported the King was unhappy with deferring thanksgiving services until August, wanting them instead on 6 July, a mere six days away, otherwise ‘it might look as if the nation was not particularly anxious to give thanks for the signing of the Peace’. Quite remarkably also, Curzon said in that meeting that ‘there was no desire on the part of himself or his Committee to have the celebrations, as they doubted whether the occasion really justified extensive rejoicing’, because the war had been so costly in human lives and suffering. This was an astonishing statement from the committee charged with organising the events. However, they were also aware from a great mass of correspondence … that the peoples of the Empire had a strong desire to celebrate Peace.

Next day Curzon told the War Cabinet that the King also wanted a ‘River Pageant’ of Royal Navy warships on the Thames. Prime Minister Lloyd George weighed in with his suggestion for a symbolic ‘catafalque … that some prominent artist might be consulted’ to design, to represent the dead, and for the soldiers and sailors to salute as they marched past (a catafalque is the raised platform that supports a coffin in a Christian funeral).

After much disagreement, the Cabinet did manage to reach two clear decisions: Thanksgiving Services should be held throughout the Kingdom and the Empire, on Sunday 6 July, with the ‘National Celebrations of Peace’ on 19 July. The latter ‘should comprise, if possible, a Military Procession of representatives of all the Fighting Services, together with an American contingent, and a River Display, the whole day to be given up to organised national rejoicings.’

So ‘Peace Day’, as it was soon dubbed by the press, was just eighteen days away, but this does not seem to have fazed Curzon, even in the face of adverse comment from some ex-service groups. An ex-soldier wrote to the Manchester Evening News to say ‘I am sure the title Peace Day will send a cold shiver through the thousands of demobbed men who are walking about the streets … looking for a job’ going on to lambast the ‘many Manchester businessmen [who] refuse to employ the ex-soldier on the grounds that he has lost four years’ experience … through being in the army’. The Federation was particularly critical, saying that ‘the first step towards Peace Celebration should be the placing of Discharged and Demobilised men in employment, and the substantial increase of Pensions and Allowances to Widows and Dependants.’ Needless to say, no such improvements were forthcoming in the short time before the big day, and most Federation branches either ignored the festivities or held their own meetings, more in protest than in celebration.

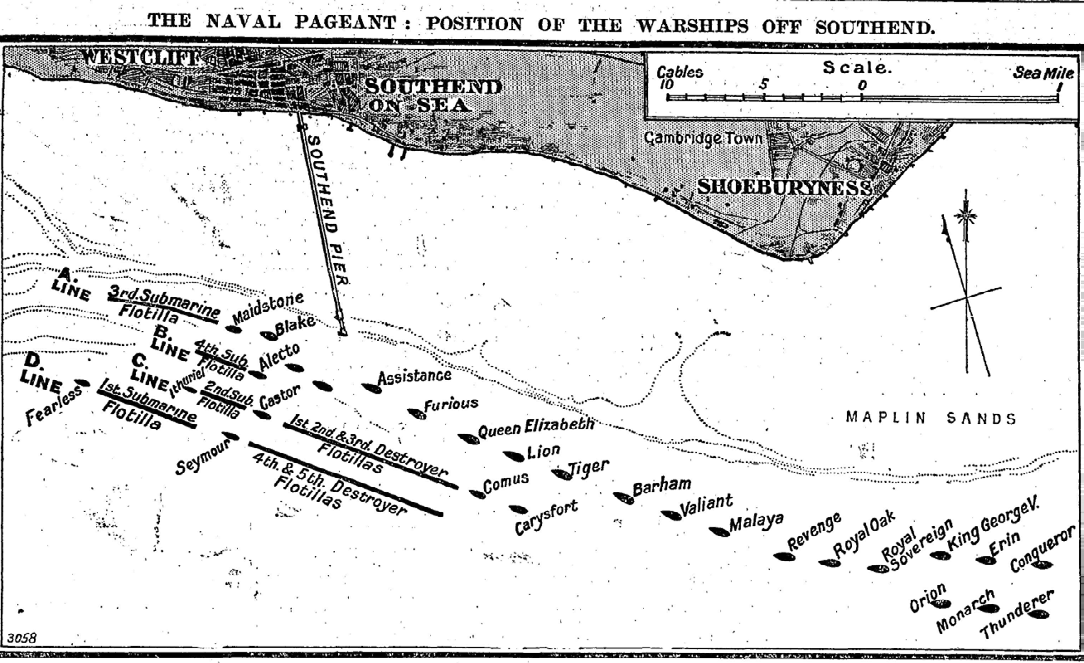

The events started with the mooring off Southend, from Thursday 17 July until the 23rd, of a fleet comprising some twenty-eight named battleships and other large vessels, along with four submarine flotillas and five destroyer flotillas.

The next day, three trains ferried 2,000 officers and ratings … to Liverpool Street Station from where headed by a band of the Royal Marines, [they] marched, amidst ringing cheers, through the city to … Kensington Gardens. This was also the base for many of the soldiers who would join the parade the next day, the camp accommodating the RAF, British infantry, pipers, bands, RAMC, ‘1914 men’, cavalry and men from more than a dozen allied countries.

Those cheering crowds were a foretaste of the growing enthusiasm for the events, notwithstanding the unhappiness of many veterans. Contemporary accounts suggest the day itself was truly extraordinary, a tribute to Curzon’s vision, superb organisation and command of detail, implemented in a very short time, including the temporary Cenotaph. This was an ‘empty tomb’, designed by Edwin Lutyens, instead of the catafalque originally proposed, and was ordered, designed and built in ten days.

Where Curzon had throughout his life adored pomp, aristocracy and royalty, for Peace Day he placed ordinary sailors, soldiers and their families at the centre. Those veterans too disabled to march were not hidden away, but instead given prime spots on the front rows, while much of the seating on Constitution Hill was kept for the mothers, widows and children of the soldiers who never returned.

People started arriving as early as 3 am, along a seven-mile route that began at the Albert Gate to Hyde Park, turned south to cross the river, winding through London south of the Thames, before returning across Westminster Bridge, past Parliament and Big Ben and north onto Whitehall, where the Cenotaph had just been unveiled, into Trafalgar Square and onto the Mall, past the Victoria Memorial where King George V and the royal party would take the salute, then along Constitution Hill to finish back in Hyde Park.

The parade of some 20,000 men and women began at 10 am, led by US General Pershing on a great brown horse, accompanied by his staff officers and company after company of infantry. They were the first to enter Whitehall where men’s eyes turned instinctively to the simple white cenotaph, with a silent bowed sentry at each corner, and they remembered those other soldiers who will march no more. Belgian soldiers were next, loudly cheered and closely followed by a smaller contingent of Chinese officers, and then the Czecho-Slavs. Next a group of French lancers ahead of Marshal Foch, on a black charger and carrying a gold-tipped baton, and so it went on: Greeks, Italians, Japanese, Poles, Portuguese, Rumanians, Serbs and Siamese. Each country’s soldiers, it was reported, brought renewed applause and cheers from the vast crowds, and then it was the turn of the British, led by Admiral Beatty and sailors of all ranks from the Royal Navy, along with naval nurses and Wrens, and members of the mercantile marine.

After the sailors came the soldiers, led by Field-Marshal Haig, with many of his generals, ahead of officers and men of ‘the Old Contemptibles’, the British Expeditionary Force of 1914. This was the curtain-raiser for groups from every part of the British Army, the Guards, Regulars, Territorials and Yeomanry, artillery crews with their field-guns, engineers, infantry, and machine-gunners. Then came ‘the Dominions’: Australians, South Africans, the Labour Corps, followed by the Women’s Legion, doctors, nurses, VADs, chaplains, and WAACs. The parade was completed by the youngest service, the Royal Air Force, the whole procession taking over two hours to pass each point along the route.

Throughout the day there were all kinds of festivities in London’s public parks - folk dancing, singing, children’s entertainments and more, culminating in a huge night-time firework display of eighty-four spectacular set-pieces. Numerous smaller events took place around the country, including a line of bonfires said to stretch from the Channel to the Cromarty Firth. Not everywhere was peaceful though, most famously in Luton, where a meeting of disgruntled veterans turned violent. The Town Hall was set ablaze, firefighters attacked and every one of them hospitalised, shops looted, and martial law imposed for three days. Coventry was almost as riotous, with the local paper reporting ‘disgraceful scenes … over one hundred casualties … boarded-up shop fronts where most of the glass has been smashed [and] looting of stocks’.

The newspapers and authorities pronounced the day a success, and just two days later the calls began for the Cenotaph to be made permanent, and within a fortnight the Cabinet agreed. The parade had included merchant navy seamen, but there was a general feeling that more should be done to mark their contribution, and accordingly another river pageant was organised for 4 August, on the Thames in central London.

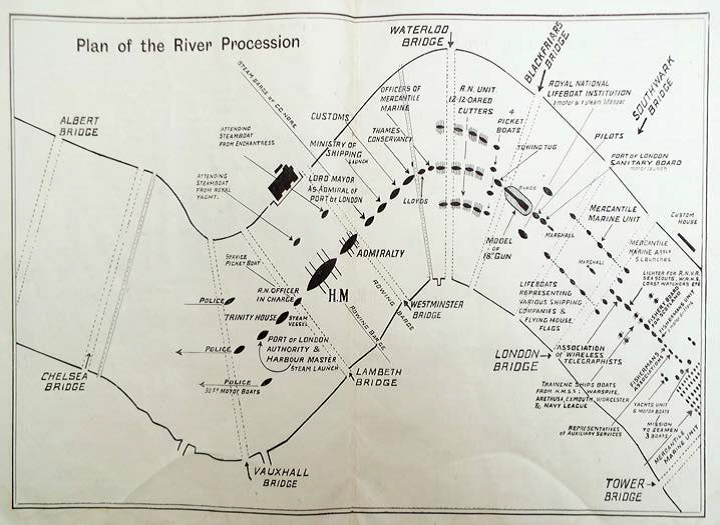

A plan of the River Procession shows a wonderfully diverse collection of ships and boats, from H.M. Rowing Barge, 230 years old and propelled by eight oarsmen, through Officers of the Mercantile Marine, Lifeboats representing various shipping companies, the Fishery Board for Scotland and many more, stretching from Tower Bridge to Vauxhall Bridge.

It must have been quite a spectacle, and a fitting tribute to all the civilian seafarers who had contributed to the war effort. Peace Day and the permanent Cenotaph were the first steps in the creation of what became over the next two years, with the additions of the two-minute silence, the Last Post and the poppy, the Remembrance Day ceremony we know today.

Mike Hally 2020

*With thanks to James Brazier for some of the detail in this report, and accompanying pictures from his personal collection.

The Victory Parade in London, 19 July 1919

Streets of London filled with thousands of adoring spectators

During the course of several marches in July 1919 the streets of London filled with thousands of adoring spectators as British regiments parade past Buckingham Palace.

Members of the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps marched through Ludgate Circus, while others showed some of the military equipment including guns and airplanes captured from the Germans being lauded through the streets for crowds of onlookers to observe.

Britain's dominions around the world played a vital role in the allies' victory in World War One, with troops from more than eighty countries sent to battlefields across the globe.

Among those who helped to defeat the Germans included 400,000 troops from Australia, 60,000 of whom were killed, 100,000 from New Zealand, which constituted approximately ten per cent of the country's entire population, and a staggering one and a half million men from India. Canada also contributed over 600,000 troops to the conflict, around 66,000 of whom were killed in action.

The Battle of the Somme, Gallipoli and the battle of Vimy Ridge were some of the bloodiest conflicts which Dominion troops fought valiantly in.

They were revered as some of the bravest men in battle, with troops from India alone receiving 13,000 medals for valour and bravery, including twelve Victoria Crosses.

Historian Santanu Das, who has written about the dominion's role in WW1, said:

“While in popular memory, the perception of the First World War remains narrowly confined to the Western Front, First World War fighting took place in Europe, Africa and the Middle East, with brief excursions into Central Asia and the Far East.”

'The litany of the names of different theatres of battle often becomes the marker for the 'world' nature of the First World War. The colonial home front - the lives of hundreds of thousands of women and children in villages across Asia and Africa who lost their husbands, brothers or fathers, and faced different kinds of hardships - remains one of the most silent and under-researched areas in First World War history.'

WFA Podcasts take off

From 1st November 2017 to the end of October 2018, the number of people listening to the podcast had quadrupled. The number of downloads went from 3,215 per months to 12,906 twelve months later. Over this period 50 episodes were produced featuring a range from the Spanish influenza, nannies in the Great War to stories on specific formation such as the 48th Division or the 8th Lincolns. A wide range of people were interviewed from interested amateurs, university professors and doctoral students. The podcast was established to further our charitable aim of encouraging interest in the Great War by reaching new audiences, mainly younger people, through emerging technologies who have tended not to attend branch meetings or join as members. The podcast over this period had 86,402 programmes downloaded with each episode receiving an average of 1,728 ‘hits’.

Given to you our members via Trustee Dr Tom Thorpe

Died in Captivity

Andrew Brooks

During the First World War Great Britain and her Empire suffered many casualties and, thanks to the tireless efforts of many individuals and organisations, they will never be forgotten. As well as those who were killed in action, who died of wounds or disease on or behind the front line there were a number who died in captivity and this article specifically remembers a few men who died whilst held in German PoW camps and hospitals.

According to the records the number of British who died in captivity was 392 officers and 10,856 men. Canada’s figures were 28 and 275 respectively and Australia 16 and 294. (Only three countries are mentioned as they cover the men mentioned in this article). It has not been possible to ascertain the cause of death for every individual man but some died of wounds received in battle, some very probably of the ‘Spanish flu’ and one man met a violent end.

Naturally the men were buried where they died and each PoW camp would have had its own cemetery. Langensalza PoW camp had its own war memorial with the names of different nationalities on four sides. After the war it was decided that the graves of the British and her Empire should be brought together into four permanent cemeteries. They are Berlin South Western, Niederzwehren, Hamburg and Cologne Southern.

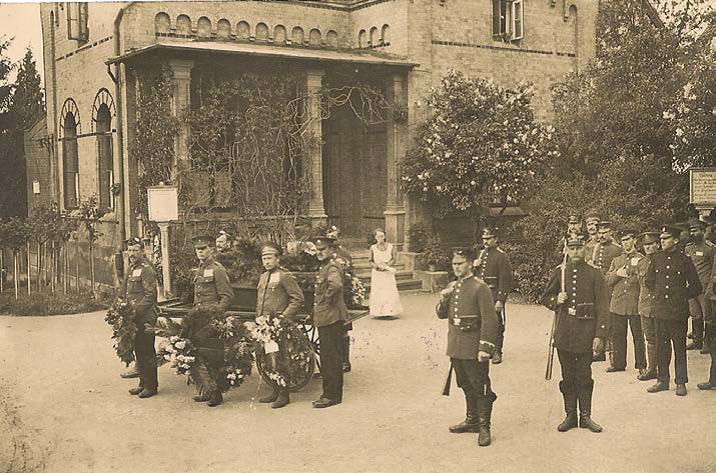

In a collection of postcards sent home from Langensalza PoW camp by Private F.Grant of the 2nd Wiltshire Regiment there were three of the funeral of Private Walter Compton 8665, 2nd Welch Regiment, aged 36 who died of wounds on the 6th May 1916. He was born at Tilbury in Gloucestershire, enlisted at Mountain Ash and had lived at 77 Church Street, Aber-bargoed, Bargoed, Cardiff with his wife Maggie before the war. It is probable that he sustained his wounds some months earlier at the Battle of Loos in September 1915. Walter went to France with his regiment on the 13th August 1914 and just over a year later on the 26th September during the aforementioned battle Colonel Prothero of the 2nd Welch and five hundred men were cut off by the Germans as they were attempting to retreat. Many men from the 8th Buffs were included in the number. The three postcards are inscribed on the reverse ‘Funeral of Walter Compton held on May 10th 1916’. Many stern looking men from a variety of British regiments form part of the cortege which includes a Russian soldier as a pallbearer. Walter is buried in Niederzwehren, Plot V11, Row J, Grave 11.

Captain Arthur Herbert Kennedy of the 23rd Battalion, 6th Infantry Brigade, 2nd Division of the Australian Imperial Force is also buried at Niederzwehren Plot V11, Row H, Grave 13. Arthur was wounded and captured during the Battle of the Somme and died a month later in captivity on the 26th August 1916. His parents were Myles and Margaret Rowley Kennedy of ‘Tarilla’, Bruce Street, Toorak, Victoria, Australia. His wife was noted as living at the same address although on another form in his service records her address is given as ‘The Pink House’ Tintern Avenue, Toorak. Arthur was born in Ulverston, Lancashire in 1877. He gave his occupation as a ‘Merchant’ shortly before embarkation in Melbourne on HMAT Euripides in May 1915 bound for Gallipoli. The 23rd Infantry Battalion landed at Suvla Bay in August 1915 but seems to have been spared taking part in any major attacks. Their only mention is when they supported the 23rd Infantry Battalion during the evacuation at Suvla.

He is mentioned on Army Form W.3121 in respect of the 6 Australian Infantry Brigade. 2 Aust. Div. 1 ANZAC Corps, 15th September 1916. This form was used to recommend men for an action (s). Four men from the 23rd Battalion on the page were recommended with one man, 2nd Lt. Richard George Moss being awarded the M.C. The other three were ‘Mentioned in Dispatches’ and one of them was Captain Arthur Herbert Kennedy. His citation reads;

For gallantry in action and conspicuous ability as a Company Commander throughout the operations at FLEURBAIX, RUE HARLE and POZIERES.

Capt. Kennedy’s work was distinguished by untiring energy, thorough knowledge and a whole – hearted devotion to duty that made him an example to all ranks in his Unit. (Reported died of wounds as a prisoner of war).

The first indication that Arthur was in trouble was a letter dated 7th September 1916. It was sent to his home address in Victoria;

23rd A.I.F. Kennedy, Capt. A.H., D. Company, (M. July 28th 1916) Informant states that on July 28th 1916 at Pozieres, there was a big attack and Capt. Kennedy was made Prisoner of War. Informant was not an eye – witness, but heard by letter from Sergt. Smith, D. Coy, now at the front Reference: S. Davis, 2614, 23rd A.I.F. D. Company, Graylingwell Hospital Chichester

This information was followed almost immediately by another letter based on an article in the Sunday Herald, a British newspaper. The paper was published on the 10th September and the following letter was sent home to Australia based on the exact words in the newspaper.

23rd A.I.F. Kennedy, Capt. A.H., C? Company, (M. July 28th 1916) Extract from ‘Sunday Herald’, 10/9/16; Still Alive Australians are glad to hear that Captain AH Kennedy, who was believed to have been killed on July 28th has written home saying he is wounded and a prisoner at Gottingen Camp, Germany. He was captured after spending a night working himself along on the ground on his back and elbows to within 100 yards of our lines.

Reference: Pte. Wm. Stewart Mitchell, 3878, 22nd A.I.F. A.Co. Bradford Hospital, 11th September 1916, Richard Walker.

Unfortunately the news was already out of date as Arthur had died of his wounds at 3.15 pm on the 26th August 1916 in the Gottingen Lazarett. It appears that his wife received the news before his parents and even before the extract in the newspaper appeared. She had received a letter informing her of his death on the 6th September from a Lt. Plews K.O.Y.L.I. who was a PoW in Gottingen. Mrs. Kennedy gave her address at this time as; Anzac Buffet, Horseferry Road, London. The two postcards of his funeral show that it was well attended with numerous wreaths.

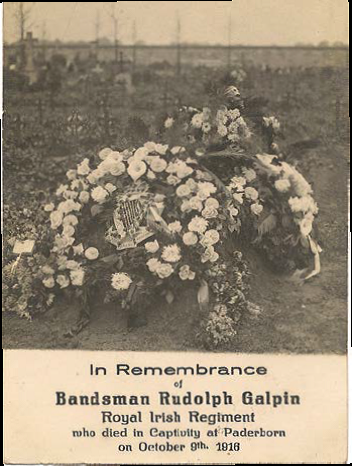

Yet another man buried in Niederzwehren (PlotV11, Row F. Grave 14) is Rudolf Galpin. He had been originally buried in Paderborn PoW camp and this is where the two postcards were taken. Rudolf died on the 9th October 1916 at a working camp (No. 112 – parent camp Senne) at Nordborchen, about three kilometres from Paderborn. Amongst the 350 prisoners were about 100 British who were in two rooms, each filled with wooden bunks. The camp was in the open countryside and all the work in 1916 was connected doing navvy work towards the construction of a new airfield. It was a military working camp and although they worked from 7am until 7pm the conditions were much better than if they had been working in a civilian run camp.

The details of the death of Rudolf Galpin were provided by Trooper N. Phelan No. 3044 of the 19th Hussars when he made a statement on his return to the British Isles on his release from captivity. According to Phelan, Galpin of the 2nd Royal Irish Regiment and a man called Hunter of the Gordon Highlanders made a plan to escape. They placed food under a truck and hid until it was dark but sentries discovered they were missing and after a search found the hidden food at 8pm. At 10pm a roll-call was held and after the Russian and French prisoners were dismissed, the British were informed that one prisoner was dead. Hunter was brought in followed by Galpin’s dead body. Hunter later described what had happened; two sentries sat down near the hidden food but instead of apprehending the men, one man shot Galpin and told the other to shoot Hunter. This man refused and simply kept him captive. The sentry who shot Galpin was called Threissmeyer and it was said that he held a grudge against Galpin for some reason. This sentry remained in the camp and even though the PoWs used to shout ‘Murderer’ after him , it did not seem to worry him!

The two postcards give different dates for his death (8th & 9 th October) and the C.W.G.C and ‘Soldier’s Died CD-Rom’ both agree on the 9th. On one of the postcards it states that he was a bandsman. According to his Medal Index Card (M.I.C.) he entered France on the 13th August 1914. Rudolf was born in Cambridge and enlisted at South Kensington. His place of residence is noted as London.

Second Lt. Charles John Beech Masefield M.C. of the 1/5th North Staffordshire Regiment was, chronologically, the next PoW to die of those discussed in this short article. Unlike the others mentioned he is remembered, not by a postcard of his grave but by a letter sent to his wife dated the 10th September 1917. It was sent by the officer in charge of the Territorial Force Records, Lichfield, but signed by 2nd Lt. H. Harper for the Lt. Colonel.

To; Mrs M.A. Masefield, Hanger Hill, Cheadle, Staffs. Madam,

I regret to inform you that a report has been received from War Office to the effect that 2nd Lieut. CJB Masefield, 5th Bn. North Staffs Regt, died 2/7/17, at the Res. Feldlaz, Le Forest, whilst in German hands. Sympathising with you in your bereavement, Yours faithfully, H. Harper

The letter would have arrived on the 11th September and immediately his wife requested a certificate of death. On the 13th September the Territorial Force Records Office explained that this could only be obtained by writing to the War Office in Whitehall. It is interesting to note that this letter was addressed to Blagg, Son & Masefield, Solicitors, Cheadle, Staffs. We would therefore assume that Charles, aged 35, and/or his father were solicitors.

Charles was obviously seriously wounded when he was captured and I am sure that he spent the time in the German Field hospital and not a PoW camp before he died of his wounds on the 2nd July 1917. His M.I.C. shows that he entered France on the 5th May 1917 and joined the battalion on the Lievin sector in front of Lens. During this time they were continuously engaged in hard fighting which culminated in the operations of the 1st July 1917. It was in this fighting that Charles must have been captured and died the next day. It could be that ‘Le Forest’ mentioned in the letter is perhaps Forest sur Marque close to Lille.

After the Battle of Gommecourt in 1916 Major-General W. Thwaites assumed command of the 46th Division and he encouraged trench raiding in order to improve the offensive spirit of the division. It was on such a raid on the 14th June 1917 that Charles won his Military Cross. The action took place near Lens. In the supplement to the London Gazette, 26th August 1917 the following citation is seen;

2nd Lt. Charles John Beech Masefield, North Staffs Reg.

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. During a raid upon enemy trenches he led his company with great dash and skill under heavy trench mortar barrage, attacking a party of the enemy single-handed and killing two of them at close quarters. At least fifty of the enemy were killed and three prisoners taken, after which he successfully withdrew his company, having shown conspicuous gallantry and good leadership throughout.

Charles was the husband of Muriel Agnes Masefield and the son of John Richard Beech and Susan Masefield. He is buried at Caberet Rouge Cemetery, Souchez in Plot V, Row H, Grave 23. His body was almost certainly one of 7,000 brought into this cemetery for reburial after the war.

Edward Woodcock died aged 55 on the 29th July 1917. He had been a PoW in Brandenburg camp since being captured on the 23rd January of the same year. Edward was the 1st engineer on the steam trawler ST Vera and along with two other ships (Agnes and George E Benson) were taken as prizes by Captain Paul Wagenfuhr commander of U44. This submarine did not survive the war as it was rammed by HMS Oracle on the 12th August 1917 and Wagenfuhr and his crew were all drowned.

The postcard of his burial has the inscription on the headstone ‘To all most dear what I would have spoken if you were near. Erected by his comrades.’ Naval and merchant seamen surround the grave and on an almost identical postcard (not illustrated) another headstone with almost the same men pay tribute to another comrade. This must have been a naval man as his cap is placed on the headstone but unfortunately the wording on the headstone cannot be deciphered. The cap band of one of the party states ‘HMS Ajax’.

Edward’s home address is given as 18 Phelps Street, Grimsby and I presume he is buried in Berlin S.W. although at the time of writing this cannot be confirmed.

Edward Fidler Pattinson was given a very fine headstone, presumably donated and organised by his comrades in Stendal PoW camp (see top of following page). He died on the 28th February 1918 and at the end of the war was reburied in Berlin South Western cemetery, Plot 1, Row E, Grave 12.

He went to France and Flanders with the 1/8th Durham Light Infantry on the 20th April 1915, No. 2606 and later No.300350. At the time of his death, aged 28, he was a corporal. The dedication on his grave is in Latin and does imply some further information.

In Memoriam Eduardi F. Pattinson 8 D.L.I. Paedagogus et pro patria miles In Belgica vulneratus et Mortuus est Stendaliae Die XXV111Feb.A.D.MCMXV111 Hoc Monumentum Datur Brittanici Comitibus ejuss in captivitate Ps CXXV1 Qui seminant in Lacrimisin Gaudio metant.

If this is translated it seems that he was wounded in Belgium and became a PoW in 1916. The last few lines are translated as ‘They that sow tears shall reap in joy’

The CWGC gives his name as Fidler Edward but I am sure that he preferred it the other way around! He was born in Haltwhistle, Northumberland and enlisted in Durham. He was the son of Mrs MAJ Pattinson and the late James W. Pattinson of 1, Woodbine Terrace, Haltwhistle.

Three almost identical postcards record the deaths of three soldiers in Gottingen PoW camp in October 1918. It is almost certain that they were victims of the influenza pandemic sweeping across Europe at this time.

Private David Bailey No.13385 of the 7th Leicestershire Regiment was born in Eckington, Derbyshire and enlisted at Dinnington in Yorkshire. His M.I.C. shows that he went to France with his battalion in July 1915. He died on the 9th October.

Private SJ Smith No. 2379862 of the 16th Canadian Scottish was born on the 19th October 1884 and died on the 13th October 1918 aged 33. Private Arthur Frank Gilbert No. 256288 of the 4th Canadian Machine Gun Corps was born on the 31st August 1887 and he also died on the 13th October.

They are all reburied now in Niederzwehern cemetery in the same row. Plot V11, Row H, Graves 9, 10 and 11.

There are many ways of ‘Remembering’ and members of the WFA all have their own personal ways. As a collector of the printed ephemera of the period I have always tried to visit the graves of those men whose letters, postcards etc. are in my possession, however I have not visited any of the German cemeteries.

References

CWGC. London Gazette 25/8/1917. Annotated version (WO/389) Captain Masefield.

Australian War Memorial. Captain Kennedy.