Chairman’s Notes, 14 July 2017

Our speaker this evening, Kate Wills considers the effect of the Great War on the musicians of the period. Several eminent composers served for both sides and the immediate aftermath saw the emergence of several iconic pieces of music. Without wishing to second guess Kate’s agenda, Ann and I have seen performances written by British composers who served in the conflict.

I am hoping that we can get a hard copy of Up the Line back into print soon. Due to commitments it has not been possible to discuss this in detail with the interested parties, but I shall keep you informed of developments. I shall also be putting full details of our 2018 speakers on the National WFA web site shortly, now that it is live.

The Imperial War Museum North’s latest exhibition is the work of Wyndham Lewis. Marking the 60th anniversary of his death and the centenary of his commission as an official war artist in 1917, Wyndham Lewis: Life, Art, War will comprise of more than 160 artworks, books, journals and pamphlets from major public and private, national and international collections.

A radical force in twentieth century British art and literature, Lewis was a brilliant draughtsman, innovative writer and satirist, and leader of Britain’s one and only avant-garde art movement, Vorticism. Spanning from the First World War to the nuclear age, Lewis’ career encompassed the most violent and chaotic period in human history. He was a controversial figure whose ideas, opinions and personality inspired, enticed and repelled in equal measure.

Those of you who came on Ann’s tour of The Sensory War Exhibition at Manchester Art Gallery will have seen some of his work. Ann and I also saw an exhibition of his portrait work in London. It was one of the most impressive collections that I have ever seen. The IWMN exhibition is on until 1st January 2018.

Germany also had one of the most talented artists in the guise of Otto Dix. His work too was represented in the Manchester exhibition. Tate Liverpool have an exhibition of his post war work during the Weimar Republic, along with contemporary photographs by August Sandel. I find Dix’s work compelling and shall make every effort to see the exhibition which is open until 15th October.

Terry Jackson, Chairman

Last Month’s Talk

Bill Fulton gave the Branch an in depth review of Albert Ball, Britain’s first air ace of the war. Ball was born in Nottingham in 1896, the son of Albert (Senior) who had risen from a plumber to become Lord Mayor of the city.

In his youth he spent much time in a shed developing his electrical and engineering expertise. He also enjoyed acting as a steeplejack and showed no fear of heights, walking unprotected around the rim of a factory chimney. His education progressed to Trent College, where he served in the OTC. Ultimately he worked in an engineering firm near his home.

In August 1914 he enlisted in 2/7th Battalion Sherwood Foresters. He was eventually was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant. Seeking action he transferred to the North Midlands Cyclists Company but was further frustrated as he saw the men he trained leave for France whilst he stayed at home.

Ball decided to take flying lessons at Hendon Aerodrome which he financed himself. This involved flying at dawn before returning to base to carry out his duties. Despite the high accident rate, he showed no fear and was unmoved by the horrendous injuries some of the pilots suffered. He obtained his pilot’s certificate in October 1915 and promptly requested transfer to the RFC.

After further training, he was awarded his ‘wings’ in January 1916. On 18 February 1916, Ball joined No. 13 Squadron RFC at Marieux in France, flying a two-seat Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2c on reconnaissance missions. He survived being shot down by anti-aircraft fire on 27 March.

His perceived aggression led to him being transferred to 11 Squadron, which was equipped with a variety of fighter scouts. He kept himself to himself, billeting in his own self-made hut. As he embarked on his fighting career, his lone wolf attitude came to the front as he also acted as his own mechanic. His first victory was on 16 May when he forced down an Albatross reconnaissance aircraft.

Ball then took over a Nieuport and commenced fighting in earnest. He began to score victories, sometimes more than one in the same day. Ball showed no fear and would often attack a group of enemy aircraft with no consideration for his own safety. This led to the award of the MC. He also had a period of reconnaissance flying at 8 Squadron

On his 20th birthday he returned to 11 Squadron as a temporary Captain and on 22 August was the first RFC pilot to shoot or force down three aircraft in one sortie. He also shot down three enemies on 28 August. By the end of the month he had accumulated 17 victories.

He then took leave and realised that although well known in France, he could still walk through his own city without being recognised. The British at this time did not publicise their Aces unlike the French and the Germans. Upon return to his unit he took over an improved Nieuport and continued to score multiple victories on the same day. At the end of September he had 31 scalps, but then, feeling the pressure of constant fighting, was given leave. He received a DSO and bar simultaneously for his exploits

The authorities used the success of Ball and the other pilots to bring some good news to the public after the losses on the Somme. He was awarded his honours by the King on 18 November and a further bar one week later. He was also made a Lieutenant. He then was posted to 34 reserve squadron in Suffolk as an instructor to pass on his experience. He also tested the new SE 5 fighter, which initially he thought inferior to the Nieuport.

In February 1917 he was made a freeman of his home city, Nottingham and became engaged to Flora Young. However, Ball desired to return to action and was appointed Flight Commander at 56 Squadron. Whilst he continued to fly his Nieuport on solo sorties, he flew the SE 5 when in formation. He had his own SE5 adapted to suite his particular preferences which include a machine gun firing downwards through the fuselage.

Throughout the spring he continued to engage and destroy enemy aircraft. On 7 May near Douai, Ball in an SE 5 attacked the Red Baron’s younger brother Lothan, who eventually landed his damaged aircraft safely. Ball was seen to enter a black thundercloud and afterwards his aircraft was seen inverted, falling and hitting the ground. Although the enemy claimed Lothan had shot Ball down, it is likely that Ball had become disorientated in the cloud and his aircraft had turned over, losing its aerodynamic properties and the engine would have cut out once inverted.

German pilots landed nearby, but found Ball already dead. They took him to a local hospital, where the doctor discovered he had a broken back and other fractures. In the strange comradery that existed between aviators, the Germans later dropped messages to confirm that he had been buried at Annoeullin. He was posthumously awarded the VC and promoted to Captain.

A detailed account of Britain’s first Ace, which was supported by a wealth of images. Ed.

100 Years Ago

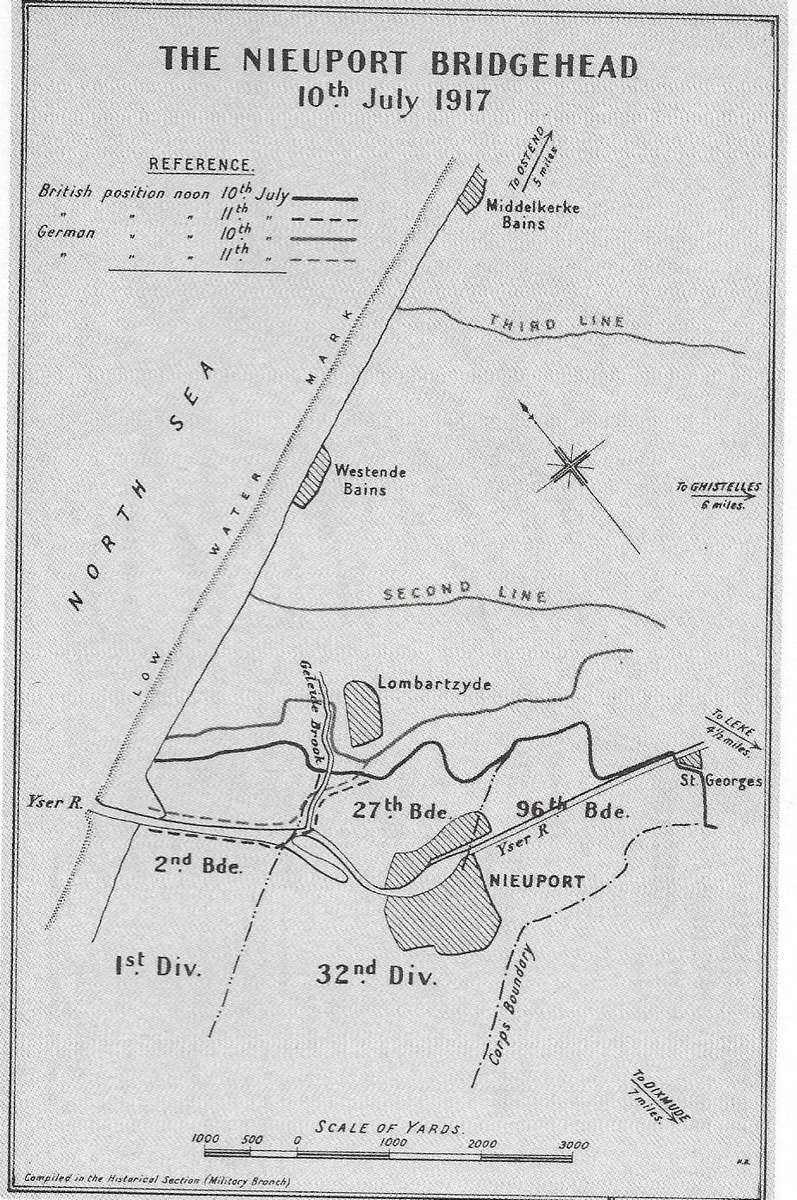

The presence of the Germans along the north coast of Belgium had been a thorn in the Allied side since 1914. Several plans had been proposed to deal with this menace. By 1917, for Operation Hush, special pontoons had been designed to take men, tanks and equipment. They were to be lashed between two monitors that would push them up the cost and on to the beaches. This would enable an outflanking of the enemy and the possibility to penetrate deep into their rear lines. After the commencement of Third Ypres, the action was due to start when Roulers was captured. The British also took over positions on the bridgehead from the French on the western bank, but the enemy anticipated that this was more than just a normal relief and that something was afoot.

Aware of the build-up, the enemy planned a pre-emptive strike (Operation Strandfest). On 6 July the Marine Korps Flandern began a three day weak barrage. Bad weather hid the German build up. At 05.30, 10 July, 3 land-based naval guns and 58 batteries opened fire on the British positions in the bridgehead. Mustard gas was used and all but one of the bridges over the Yser were destroyed. This isolated 1/Northants and 2/KRRC on the far left flank with the loss of communications. British counter battery returned fire but the enemy had good shelter. As the German batteries continued, at 20.00 the Germans attacked along the coast outflanking the British units who, by now were only at 20% strength. German marines with flame throwers mopped up and the British were overwhelmed. Only 4 officers and 64 men reached the west bank of the Yser. British losses were 1,300.

Aware of the build-up, the enemy planned a pre-emptive strike (Operation Strandfest). On 6 July the Marine Korps Flandern began a three day weak barrage. Bad weather hid the German build up. At 05.30, 10 July, 3 land-based naval guns and 58 batteries opened fire on the British positions in the bridgehead. Mustard gas was used and all but one of the bridges over the Yser were destroyed. This isolated 1/Northants and 2/KRRC on the far left flank with the loss of communications. British counter battery returned fire but the enemy had good shelter. As the German batteries continued, at 20.00 the Germans attacked along the coast outflanking the British units who, by now were only at 20% strength. German marines with flame throwers mopped up and the British were overwhelmed. Only 4 officers and 64 men reached the west bank of the Yser. British losses were 1,300.

The next day Rawlinson ordered a counter attack. However, Lt. General Du Cane (XV Corps) persuaded him that whereas immediate counter attacks often succeeded, delayed ones usually failed against prepared positions. It would be better, he argued, to consolidate the defence and wait for more artillery. He also convinced Rawlinson that any attack should await a progression of the main Ypres offensive.

The action caused Haig to reassure the perturbed War Cabinet via the CIGS that this setback would not affect the original plan. However, it was revised to comprise an attack north of the narrow front still retained and the coastal attack would then proceed as before. He also insisted that British artillery had to master the enemy guns. As Haig believed that by 8 August the main assault would have made enough progress to make the scheme feasible, he gave Rawlinson the go ahead.

From the Official History-Ed