Up the Line

May 2016

Chairman's notes

Good evening and welcome to the May meeting. A week ago I attended the WFA AGM at the Fleet Air Arm Museum in Yeovilton. Due to the time factor, these notes have been submitted to Ralph for UTL before the event and I hope to be able to advise you of any major developments tonight. This will include any details which we have been given of the Heaton Park event on 1 July.

The build up to First Day will be gathering momentum. Hopefully, some of the more reputable historians will have been approached by the media for a balanced assessment, but I am sure the sensationalists will have to have their say. Fortunately, we are able to hear from one of the most eminent authorities on the subject in June when John Bourne looks at 1916.

Tonight I am very pleased to introduce Jonathan Bell as our speaker. Both he and Captain Lesley Oldham have recently provided us with excellent new facilities and equipment. Strictly speaking they are our hosts, but I know we will accord them our normal warm welcome. Jonathan will educate us on the work of the RAMC and how it has adapted since its early days. A quick look at the CWGC website indicates that over 7,000 RAMC personnel were killed in the Great War and nearly 3,000 in the Second World War. The RAMC also contained the only man be awarded the VC twice during the first conflict. Like me, I am sure you are looking forward to this talk.

Terry Jackson. Chairman.

Last month’s talk

During the first few days of the Great War in August 1914, the Germans’ plan to wheel the Allies into a corner seemed to be working. However by the beginning of September they retreated at the Marne. Although they were able to hold the Allies on the Aisne, for most serious historians, this was the moment at which Germany would not be able to win the war.

The decision involved a relatively junior officer of Von Moltke’s staff. Ross Beadle gave an in depth analysis of how the British and French were able to retrieve what had looked like an inescapable defeat.

By early September the Germans had believed they had effectively won. Their Schlieffen Plan had put them in pursuit mode in the west. France’s Plan XVII was basically to enable assembly and concentration of forces against the heart of the enemy and had failed. However, von Falkenhayn, who would eventually become Army Commander, made the pertinent comment that if the Allies were being routed, then where were all the prisoners?

Germany’s First Army (von Kluk) was the most westerly of the seven involved. It also had to cover the furthest distance. (Kluk’s Chief of Staff, von Khul was the effective organiser). Along with the Second (von Bulow) and Third Armies (von Hausen) it had been pursuing the BEF and the French southwards from Belgium via Mons and Le Cateau. Their original success was emphasised by using reserves in the attack. French intelligence had discounted enemy reserve units of being involved. The French had also been drawn into fatal attacks against the four other easterly Armies in the Battle of the Frontiers.

The French belief that attack and ‘elan’ would prevail, even against hastily prepared defences cost them dearly. Their Artillery merely opened fire on the day of assault, leaving the attacking infantry to face the withering fire of machine guns and artillery.

General Joffre gradually understood the position. He held the positions on the right and built up units on the left. He travelled around the French positions and sacked 162 generals that he held responsible. He required Lanrezac’s Fifth Army to fight a holding action at Guise (d’Espèrey eventually led the attack when Lanrezac was sacked) and the BEF to hold its position. Sir John French initially told Joffre that he intended to retreat and refit. This caused Kitchener, now Secretary of State for War to visit French and tell him he had to comply with Joffre’s request. This incident caused antagonism between the two British soldiers. Kitchener was now a government official and his appearing in uniform was badform. A subsequent impassioned appeal by Joffre to French persuaded the British commander to support him.

Fortunately, this resolved the situation and Joffre was able to plan his actions. A new French Army (Sixth) was created under the control of retired General Gallieni. By now France had better access to supplies, guns and communications. Germans had to walk 440 kilometres, whereas the French rail network brought troops to the Front. By now the Allies also had superiority in battalions and guns.

The next phase of the fighting was to prove crucial. von Moltke stayed well behind the front and never had grip on the situation. Thus, despite being instructed to mark time and wait for Second Army,First Army chased the French, opening a gap between the two German forces. On 6th September, the new French Sixth Army marched, aided by troops being brought up by taxis and buses from Paris. von Kluk recalled his troops to deal with this threat, which would enable the BEF to exploit the gap caused by the turning motion of von Kluk’s units.

As von Moltke refused to travel, he relied on junior staff officers to feed him with reports and they were empowered to give advice to much senior commanders. This brought Staff Officer Lieutenant-Colonel (German equivalent) Richard Hentsch into the picture. He had been touring all the seven armies and reporting the progress to von Moltke. Hensch assessed the situation and advised a general retreat. Although the situation was difficult, it was not as dire as the pessimistic Hentsch believed. (The BEF was slow to exploit its opportunity). Also, the communications between the German Army leaders had been virtually non-existent and they complied. Thus the Germans fell back to the Aisne, dug in and trench warfare began. The failure of 1914 cost von Moltke his command and he was replaced by von Falkenhayn.

After the war only von Khul was able to cement his actions favourably. Von Moltke died in 1916, Hensch aged only 49 in 1918, following an operation, von Bulow in 1921, von Hausen in 1922 and von Kluk in 1934. Von Khul lived to be 102 and up to his death in 1952, he ensured his story held sway.

An excellent presentation given by Ross on probably the most crucial action in the War. 1914 is a fascinating year and usually ignored by popular historians and the media for the intermediary years of Trench Warfare.

Ed

100 Years ago

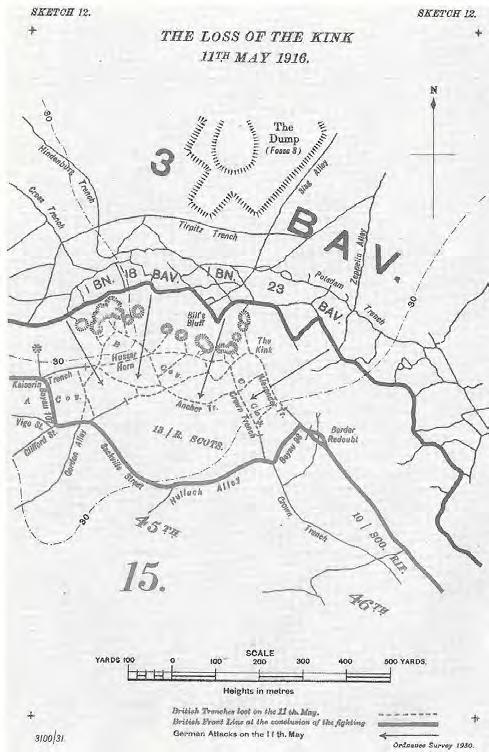

The loss of the kink, 11th May 1916

The British line, just south of Hohenzollern Redoubt at Loos, was a blunted salient 400 yards wide. It went across a slight depression towards Fosse 8 which had seen intense fighting in 1915. There were two projecting shoulders ‘Hussar Horn’ to the left and ‘The Kink’ to the right. Fosse 8, behind the enemy lines overlooked the salient. The Kink was subject to continual shelling. There was tunnelling activity and mines which had left several craters in No Man’s Land. These had been occupied by both sides, although British underground activity had secured all except one of the craters north of the Kink. There had been a short period of inactivity but on 11th May th enemy shelled the area extensively concentrating on the Kink although to cause confusion, Hohenzollern Redoubt was also shelled. At 5.45pm a massive bombardment was launched on the Kink, including gas. A shell landed on the HQ of 13th Royal Scots in the prime position. All the battalion staff were killed or wounded and the chain of command was effectively destroyed. The enemy were able to penetrate the position and also Anchor Trench. The Scots retreated to Sackville Street and the Germans were able to capture 39 miners from below the surface.

Unfortunately, British artillery continued to fire on the Germans’ original positions, so the invaders were able consolidate their newly gained ground. At 6.30pm the 13th Royal Scots attempted to bomb the enemy out of their positions, but were hit by machine gun fire and failed. By the early hours of 12th May the British had replaced the now destroyed Sackville Street with another trench. After a few futile attempts to improve the position in the following days up to the 15th, the British consolidated in their new positions.

The assault had been carried out by 18th Bavarian Regiment in order to improve their position, as originally they had been effectively overlooked by the British. Their preparations had been carefully made over several weeks, including the provision of deep dugouts for shelter before the attack.

The Royal Scots casualties over the several days were- Officers 10 KIA, 5 wounded and 1 missing. Other ranks, 14 KIA, 60 Wounded and 152 Missing. Many of the missing had been buried by the initial bombardment. German losses were 2 officers and 12 other ranks KIA, 57 wounded.

From Official History 1916 Vol.1. Ed

Memories of our won WWI veterans has been put into the "Articles" section - here

Next issue - word docs, cuttings, jpegs etc to Terry by 6th June. His email is on the "Venue" page - you will need to click on the link there.