Newsletters

- Details

- Category: Newsletters

Last Month’s Talk

The Branch always looks forward to the talks by Professor John Derry. Once again they were not disappointed as he analysed the effectiveness of the German High Seas Fleet.

British domination of the seas had existed for many years. However, the works of the American Alfred Mahan in the late 19th century on sea power influenced the German Von Tirpitz that Germany should have a strong navy if it was to consolidate its position as a world power. This influenced both the former and Kaiser Wilhelm II that it needed an effective navy to secure this. The Kaiser, being the eldest grandchild of Queen Victoria and jealous of her fleet believed the German state, unified after the Franco-Prussian War, should have a fleet as effective as the Royal Navy. However, Mahan’s views would be questioned in Germany. Many thought that the security of the land mass of the new nation was more important. The dominance of the German Army brought about friction between the two services, especially when it came to funding. Germany wanted to avoid a concurrent war on two fronts, and Army expenditure would suffer if funds were diverted to sea power.

The recovery of France from its defeat in 1871 and its growing partnership with Russia brought about the Schlieffen Plan, as amended subsequently by von Moltke the younger, to offset this concern to the German Army. Nevertheless, the Kaiser still wanted a Grand Fleet to rival his Grandmother’s Navy. Thus Germany began to expand its sea power which internally led to poor relations between its two armed forces. Unfortunately, the development of the Dreadnoughts by Britain pushed it ahead of its continental regal cousins. By 1914 Britain had superiority at sea. This was necessary, but also a structural problem, as it had to protect is overseas possessions, whereas, whilst Wilhelm II wanted colonial equality, it was still behind Perfidious Albion in overseas possessions. This brought about fundamental differences in the construction and nature of the two fleets. Britain had to plan for global protection, whereas the Germans would basically be active in the North Sea.

Britain had superiority by 1914, but German ships were of very good quality and helped by excellent electrical and chemical engineering. Their range finder was also superior. Thus Germany’s aim was to damage the British Navy to the extent that its command of the seas was reduced. Mahan’s ideas on a fleet in being meant Germany’s navy could not be ignored by Britain.

Early in the war Germany did have some success with raiders and action at Coronel when Admiral Craddock’s rash attack in November 1914 saw the sinking of the two main British warships Good Hope and Monmouth. However, the situation was reversed at the Falklands a month later when a superior British force sank the four German Capital ships previously involved.

This caused the German Navy to concentrate on submarine warfare, although no British soldiers were ever lost on ships transporting them to the Western Front. (Nor did the USA lose any from 1917). Initially, surface raids were carried out on England’s North East coast and there were civilian casualties in Hartlepool and Scarborough. This was one of the many self-incriminating acts that was to reflect badly on Imperial Germany’s conduct of the war and played on by the Allies.

Germany then turned to submarine warfare as a means of affecting British supplies and countering the Blockade by the Royal Navy which increasingly restrained the supply of essential products to German ports. However, the cruelty of German military forces initially seen in the invasion of Belgium and France was also levied against the perceived brutality of Germany in actions such as the sinking of the Lusitainia in May 1915. This was aggravated by the death of 128 Americans, notwithstanding the German accusation that the ship was carry war ordnance. It tempered the German desire to hit back at the continuing effect of the Royal Navy’s blockade.

The continued bitterness between the two German military bodies increased as the Army compared its high losses on both European Fronts and the lacklustre efforts of their naval counterparts. However, in early 1916 the two nations were to face one another two major conflicts on land and at sea. As the Britain and its Allies were planning for an attack on the Somme, Germany was preparing to try to relieve the increasingly burdensome effect of the Royal Navy Blockade. The onset of what was to become known as the Turnip winter encouraged a plan to lessen the Royal Navy’s dominance of the North Sea.

The only major sea battle between the two powers during the war has been repeatedly analysed and studied by historians ever since. Whilst the Royal Navy suffered the heavier losses, it did not bring about the end of the naval blockade nor the destruction of the Royal Navy. Poor intelligence from Room 40 and the ignoring of safety rules to achieve a faster rate of fire caused several British capital ships to suffer shattering explosions as enemy shells penetrated ammunition magazines. Although British losses at Jutland were heavy, it ensured the German High Seas fleet never lived up to its name for the rest of the war as it languished in harbour.

The lack of a total victory caused the Germans to return to unrestricted submarine warfare in early February 1917. This act which angered the Americans was made worse by the subsequent release by the British of the Zimmerman telegram. The British had intercepted a message by the German Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs to the Mexican government promising help to Mexico to recover lost lands in the USA if they helped Germany should it be attacked by the USA. Although British actions were basically illegal, by releasing it at a relevant time it fuelled the resentment in the USA over Germany’s actions and contributed to the former’s entry into the war.

At the time this was critical as U boats were dominating the sea war. The provision of protection by the USA navy and forming of convoys in protected water helped relieve the effects of the U boat campaign. It also eventually brought to the field a huge source of fresh manpower that offset the demise of the Russian forces. This led to the final gamble by the German army to win in the spring of 1918 before our new Ally could have an effect on the war. During the German advances their soldiers were shocked to see huge stacks of food supplies left by the BEF, as they had been told the submarines were causing starvation in England and on the Western Front. This was exacerbated by continual stories of their families actually facing starvation at home. This was eventually to lead to the Armistice in November 1918.

Despite its qualities, the High Seas Fleet was a white elephant. Money spent on it was denied to the Army as it fought a war on two fronts. The Fleet, excluding submarines, was cooped up in port. Morale declined with poor conditions and lack of leave and leisure. Mutinies and Sailors Councils added to the tensions. In 1918 The Kaiser was forced to abdicate and flee to Holland.

The essential battleground for the determination of the First World War was always the Western Front. Despite the efforts of Churchill (Half American) and Lloyd George (a contrived Welshman), it was possible to end the war in the West and force a cessation in the other theatres.

Professor Derry observed that Bismarck would not have allowed this to happen as it was a distraction to the land war. He also quoted Foch who posed the question as to why did Germany take the risk and cost of funding a war, when given its increasing industrial and financial might it would soon have been the dominant country in Europe. Unfortunately another erstwhile leader was to make the same mistake 25 years later, when the inanimate namesake of the above was to be involved in a similar naval engagement.

Yet another superb and engaging talk by probably our favourite speaker which kept the audience spellbound.

Terry

- Details

- Category: Newsletters

Chairman’s Introduction

Welcome to our August meeting and we are pleased once again to have for your enlightenment the very popular speaker on the WFA circuit, Professor John Derry. John’s subject this evening is the German High Seas Fleet: A case of futility.

One of the reasons for growing Anglo-German antagonism before 1914 was the German decision to build a modern battlefleet, with the consequent Anglo-German naval race. Though the German High Seas Fleet was an excellent navy – well-trained officers and men, superbly designed capital ships and outstanding gunnery – it was never able to break the Royal Navy’s command of the North Sea.

Though the 1917 submarine campaign inflicted immense damage on allied and neutral shipping, it also brought the USA into the war, with catastrophic consequences for Germany. Eventually morale in the German fleet collapsed and the sailors mutinied. Following the German defeat in November 1918, the Allies interned the bulk of the High Seas Fleet in Scapa Flow, where it was ultimately scuttled by its crews in June 1919, days before the belligerents signed the Treaty of Versailles.

Why, then, was the High Seas Fleet built? Did it have any coherent strategy? Or was it (as some German generals claimed) a massive diversion of much needed funds and material from the enemy? These are some of the issues which John Derry will address in his talk.

Last Month’s Talk

Dr Peter Hodgkinson presented the branch with a detailed and absorbing account of the clearing of the battlefields and clarified some of the most often misinterpreted evidence found in field graves.

CWGC cemeteries are well known to Great War students. The communal grave was well documented in the Press. In one case, there seemed to be a linking of arms of several men and it was suggested some more isolated were officers. This was pure journalistic speculation. Soldiers were routinely buried with their arms across their chest. As time passed and the bodies settled the arms would fall and create this illusion. The unequal spacing in parts could be due to variations in the rate of interment.

In previous conflicts mass graves had been common, but the expansion of modern warfare gave rise to a more formal approach. The American Civil War and subsequent conflicts led to a social desire to give nations’ fallen a permanent resting place annotated with details of its incumbent.

The Great War found Britain unprepared for the number of losses commencing with the early days of the war. In the first two years on the Western Front, both sides had generally settled to a static position pending the discovery of a way to outsmart the overpowering strength of defensive ordnance.

Britain’s initial trial of will occurred on the Somme in the summer of 1916. The heavy casualties on 1 July are now well known. At its cessation over 660,000 British "other ranks" and 41,000 officers were dead. Of those, 106,973 were missing, 53,409 bodies were unknown, 53,564 were lost and, in total, at least 250,000 were not in known graves.

The increasing concern of recording casualties led to SS456 (Aug 1916) indicating how burials should proceed. The soldier’s pay-book and personal belongings with one of the identity discs were to be removed. Boots were to be removed for salvage. The task was very unpopular as many bodies had deteriorated as to be almost unrecognisable. The task continued after the Armistice. Experience of where to dig was necessary- rifles in the ground, partial remains on the surface, rat holes and surface discolouration were indicators.

There were various ways a soldier could be identified. The most common (61.7%) was from the personal id discs. Personal items, especially letters could indicate the soldier. Equipment might be inscribed and AB64 (the paybook) would fulfil this. Some unknown soldiers may have been ascribed to a country or unit by the type of clothing, or regimental badges. Rank shown by pips or stripes might narrow the search.

The efficiency varied from unit to unit- Australians being unreliable and subject to indiscipline. Many soldiers complained of the conditions under which they had to work and of the terrible state of some bodies

A very detailed and well study of an often forgotten past of the conflict. TJ

Simpson’s Donkey

Ann and I recently visited Newcastle. Whilst there, we were pleased to be able to go for a meal with tonight’s speaker, Professor John Derry.

Our main purpose was to walk the trails of the Great Exhibition of the North, which took up an entire day of our visit. On the final day we visited the Roman fort Segedunum at Wallsend. We then crossed the Tyne by ferry from North Shields to South Shields. The purpose was twofold as Ann’s mother was born there and we visited another Roman fort, Arbeia.

Before returning to Newcastle by Metro, we stopped for something to the town centre for something to eat. It was there that we noticed a new monument to John Simpson Kirkpatrick. He was born in the town, but jumped ship in Australia whilst working as a sailor.

He dropped his surname and joined the Australian Medical Corps and went to Gallipoli. There he became well known by using his donkey to bring back wounded despatches. For this he was Mentioned in Despatches. On 19th May 1915 he was killed by machine gun fire.

After the war he became legendary and as is often the case his stature was enhanced by the media. He used more than one donkey and whilst undoubtedly saving many lives, his donkey was used to bring men from gullies not the beaches. Many more stretcher bearers were killed or wounded in that relatively open area.

Subsequently there was a campaign to obtain a medal or commendation for his actions. This was not accepted as all the other stretcher bearers that received an award were given M-I-D and were rightly considered to be as equally brave.

TJ

100 Years Ago

On 8th August 1918, British and French forces attacked on the First day of the Battle of Amiens. This counter offensive to the final German assault began the period of Allied attacks known as the 100 Days. The element of surprise and lack of bombardment caught the enemy unawares. Their own infantry was neutralised by counter-battery fire and the attack spearheaded by tanks.

However, despite the successes especially in the number of German soldiers who surrendered, the loss of tanks and relative lack of bombing success on bridges by the RAF meant the war was still a going concern.

The battle continued on the 9th. Semi-open warfare brought about communication problems. Where there was the possibility of wire-tapping, runners or horses were used but were vulnerable to enemy fire. Many of the tanks had broken down or been destroyed

On the 10th, the focus of the Amiens Offensive shifted to the south of the German-held salient. Here, General Georges Humbert’s French Third Army moved toward Montdidier, forcing the Germans to abandon the town and thus permitting the reopening of the Amiens to Paris railroad. The first stage of the offensive was brought to a close in the face of increasing German resistance on the 12th.

TJ

- Details

- Category: Newsletters

Last Month’s Talk

Michael LoCicero presented an adaptation of his recently published book ‘Midnight Massacre’. This had been his university thesis and he brought light to this generally unknown action

The night action of 1/2 December 1917 during the First World War, was a local operation on the Western Front, in Belgium at the Ypres Salient. The British Fourth Army (re-named from the Second Army on 8 November) attacked the German 4th Army. The Third Battle of Ypres (31 July – 10 November) proper had ended officially on 20 November but the attack was intended to capture the heads of valleys leading eastwards from the ridge, to gain observation over German positions.

On 18 November the VIII Corps on the right and II Corps on the left (northern) side of the Passchendaele Salient took over from the Canadian Corps. The area was subjected to constant German artillery bombardments and its vulnerability to attack led to a suggestion by Brigadier C. F. Aspinall that, either the British should retire to the west side of the Gheluvelt Plateau or advance to broaden the salient towards Westroosebeke. Expanding the salient would make the troops in it less vulnerable to German artillery-fire and provide a better jumping off line for a resumption of the offensive in the spring of 1918.

The British attacked towards Westroozebeke on the night of 1/2 December but the plan to mislead the Germans by not bombarding the German defences until eight minutes after the infantry began their advance came undone. The noise of the British assembly and the difficulty of moving across muddy and waterlogged ground had also alerted the Germans. In the moonlight, the Germans had seen the British troops when they were still 200 yd (180 m) away. Some ground was captured and about 150 prisoners were taken but the attack on the redoubts failed and observation over the heads of the valleys on the east and north sides of the ridge had not been gained.

The speaker calculated that the 8th Division losses from 2 to 3 December were about 552 men; the 32nd Division had 1,137 casualties and infantry regiments 117, 94, 116 and 95 had about 800 loses. The Official History made no mention of the action.

This was an excellent presentation which included the reason for the assault and the build up to the actual action. The full account can be read in the speaker’s book* which is well researched fully delves into the reasons for its conception, the preparations and actions of both sides

*‘A Moonlight Massacre. The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge 2 December 1917’.

TJ

100 Years Ago

Quentin Roosevelt (19 November, 1897 –14 July, 1918) was the youngest son of President Theodore Roosevelt and First Lady Edith Roosevelt. Family and friends agreed that Quentin had many of his father's positive qualities and few of the negative ones. Inspired by his father and siblings, he joined the United States Army Air Service where he became a pursuit pilot during World War I. Quentin was only four years old when his father became president, and he grew up in the White House. By far the favourite of all of President Roosevelt's children, Quentin was also the most boisterous. With American entry into World War I, Quentin thought his mechanical skills would be useful to the Army. He dropped out of college in May 1917 to join the newly formed 1st Reserve Aero Squadron, the first air reserve unit in the nation. He trained on Long Island at an airfield later renamed Roosevelt Field in his honour.

Finally sent to France, Lt. Roosevelt first helped in setting up the large Air Service training base at Issoudun. He was a supply officer and then over time ran one of the training airfields. Eventually he became a pilot in the 95th Aero Squadron, part of the 1st Pursuit Group. The unit was posted to Touquin, France and, on July 9, 1918 to Saints. Here he roomed with supply officer Ed Thomas. Roosevelt had one confirmed kill of a German aircraft he shot down on July 10, 1918. Four days later, in a massive aerial engagement at the commencement of the Second Battle of the Marne, he was himself shot down behind German lines.

Captain Eddie Rickenbacker, Commander of the 94th Aero Squadron (also known as the "Hat-in-the-Ring" Squadron), in his memoirs described Roosevelt's character as soldier and pilot in the following words:

"As President Roosevelt's son he had rather a difficult task to fit himself in with the democratic style of living which is necessary in the intimate life of an aviation camp. Everyone who met him for the first time expected him to have the airs and superciliousness of a spoiled boy. This notion was quickly lost after the first glimpse one had of Quentin. Gay, hearty and absolutely square in everything he said or did, Quentin Roosevelt was one of the most popular fellows in the group. We loved him purely for his own natural self”.

"He was reckless to such a degree that his commanding officers had to caution him repeatedly about the senselessness of his lack of caution. His bravery was so notorious that we all knew he would either achieve some great spectacular success or be killed in the attempt. Even the pilots in his own flight would beg him to conserve himself and wait for a fair opportunity for a victory. But Quentin would merely laugh away all serious advice."

Quentin's plane (a Nieuport 28) was shot down in aerial combat over Chamery, a hamlet of Coulonges-en-Tardenois (now Coulonges-Cohan) He was felled by two machine gun bullets which struck him in the head. The German military buried him with full battlefield honours. Since the plane had crashed so near the front lines, they used two pieces of basswood saplings, bound together with wire from his Nieuport, to fashion a cross for his grave. For propaganda purposes, they made a postcard of the dead pilot and his plane. However, this was met with shock in Germany, which still held Theodore Roosevelt in high respect and was impressed that a former President's son died on active duty. According to his service record, the site was at Marne Grave #1 Isolated Commune #102, Coulongue Aisne. The French government awarded him the Croix de Guerre with Palm.

Three German pilots have been credited with Quentin's "kill" at various times, and all three of them may have been his killer. Lt. Karl Thom of Jasta 21, one of the greatest German flying aces of the war, was in the vicinity and had confirmed kills nearby; he was often credited with Quentin's downing, but never claimed the kill. Lt. Christian Donhauser of Jasta 17 claimed credit and publicized himself as Quentin's killer after the war. Sergeant Carl Graeper of Jasta 50 also claimed credit, but if he did fire the fatal shots, it was his only kill during the war. All three of them may have been in the dogfight which claimed Quentin's life.

TJ

Web ed footnote: Quentin reputedly was only able to become a pilot because he memorised the eye-test chart, as otherwise his eyesight would have stoppped him doing so. This was the suppposed cause of his death as he did not recognise the other planes as being German. After WWII, he was re-interred in the American ABMC cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer, to lie next to his brother Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr who died of a heart attack in Normandy, just after D-Day.

- Details

- Category: Newsletters

Last Month’s Talk

Greg Baughen presented an excellent and well sourced talk on how the Royal Flying Corps set about tackling the enemy air force

Long before the first shots were fired in the Great War, army generals knew that aircraft were going to play a crucial role in future wars. They also realised that some way of shooting down enemy planes had to be found. Designers and engineers were soon struggling to find a way of doing this.

Inspired by the Royal Navy's dreadnoughts, the Royal Flying Corps planned to rule the skies with their own aerial battleships. It was an approach that proved to be a mistake and would delay the development of the single-seater fighters that were needed to challenge the German Fokkers and Albatrosses. The Pup, Camel and S.E.5a eventually emerged and helped save the day, but the battleship fighter was never abandoned completely. Even at the end of the war, there were still plans to develop them and the concept would continue to influence British fighter design long after the First World War.

The talk also considered the technical problems that affected the design and stability of the aircraft. Reflecting the idea of an aerial gunship, the designers tried to create an aerial equivalent of a naval gunship. The problems of recoil from firing a cannon where all too obvious, and although ‘pushers enabled a gunner to be placed at the front of an aircraft it was not a satisfactory solution. A number of specialist gun ships were considered but all were far too cumbersome to be of use

To contest the skies with the enemy, a scout (fighter) would be limited by weight restricting designs to a single engine. The contemporary designs were extremely lightweight and could not support heavy ordnance. Lewis guns could be attached to the upper wing, but required the pilot to stand when firing. The ideal was to be able to straight ahead. The only problem was the propeller.

The French pilot Roland Garros experimented with deflector plates on the propeller that caused the bullet to shoot away at an angle when it hit the propeller. On 1st April 1915 Garros achieved his first success with this modification.

Garros was forced to land soon afterwards and the Germans captured his aircraft. They employed the Dutchman Fokker to consider this problem and he eventually came up with an interrupter gear that stopped the machine gun from firing when it was in line with the propeller. This proved a great success and gave the enemy the upper hand until the Allies were able to develop their own.

An excellent detailed talk that included some remarkable photographs of experimental gunships and the like. Ed

100 Years Ago

The Third Battle of the Aisne (Blücher-Yorck) had petered out on 6th June 1918. Victory seemed near for the Germans, who had captured just over 50,000 Allied soldiers and over 800 guns by 30 May 1918. But advancing within 56 kilometres (35 miles) of Paris on 3rd June, the German armies were beset by numerous problems, including supply shortages, fatigue, lack of reserves and many casualties.

Although Ludendorff had intended Blücher-Yorck to be a prelude to a decisive offensive (Hagen) to defeat the British forces further north, he made the error of reinforcing merely tactical success by moving reserves from Flanders to the Aisne, whereas Foch and Haig did not overcommit reserves to the Aisne. Ludendorff sought to extend Blücher-Yorck westward with Operation Gneisenau, intending to draw yet more Allied reserves south, widen the German salient and link with the German salient at Amiens.

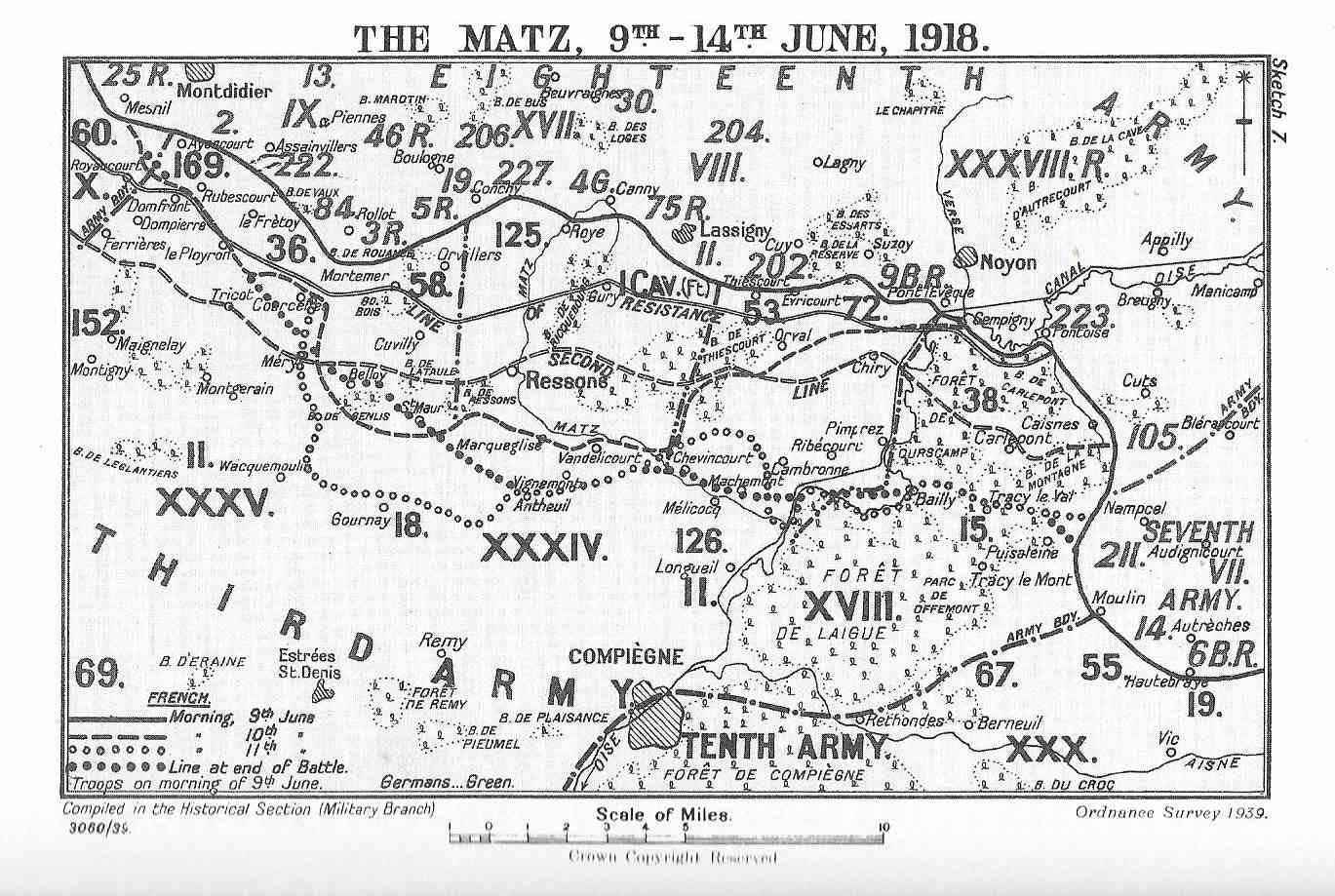

The French had been warned of this attack (the Battle of the Matz) by information from German prisoners, and their defence in depth reduced the impact of the artillery bombardment on 9th June. Nonetheless, the German advance (consisting of 21 divisions attacking over a 23 mi (37 km) front) along the Matz River was impressive. It resulted in an advance of 9 miles (14 km) despite fierce French and American resistance. At Compiègne, a sudden French counter-attack on 11th June, by four divisions and 150 tanks (under General Charles Mangin) with no preliminary bombardment, caught the Germans by surprise and halted their advance. Gneisenau was called off the following day. Losses were approximately 35,000 Allied and 30,000 German.

Although the Germans tried one last offensive Friedensturm in mid-July, their force was spent and the Allies would be soon ready to launch their ultimate attack in early August, leading to the ‘100 days’ during which the Germans realised the game was up and ultimately sued for peace in early November

Ed.

- Details

- Category: Newsletters

Chairman’s Introduction

Thanks Terry!

May I firstly take this opportunity to compliment and say a big “Thank You” to the retiring Chairman, Terry Jackson, who has reigned for ten years, enabling us to have regular monthly meetings and listen to an endless cornucopia of WW1 subjects during the Centenary period and long before of course. Well done Terry and you, and Ann, can now sail off into the sunset, if you can find the time between your stints of invigilating and speeding around Lyme Park in a mini-bus?

Looking forward my grateful thanks to Andy McVeety who has agreed to carry on as our Hon. Treasurer and, due to closure of RBS, is already embroiled in moving the Branch fortune to an alternative safe haven.

Phil Hamer has agreed, nay nominated himself, to carry on in the role of “General” dogsbody. He will continue to ensure that all necessary wiring is safely positioned and that ‘we’ will be educated about the Great War and I’m sure he’ll keep the speakers on their toes with suitably testing questions.

Also, we have Joan Tomlinson who has always greeted members as they enter the room with the obligatory raffle tickets and will continue to organise the draw and prizes. We seem to have accumulated a large number of books and DVD’s so she will look at ways and means to and move these on asap.

Our steward, Alan, will continue to prepare the coffee/tea/biscuits in the bar after the evening’s talk.

I look forward to my first official meeting as new Chairman of the Branch and I encourage and welcome all who might read this to attend and be enlightened by our guest Greg Baugham speaking on the aviation aspect of Great War history.

My intention is to carry on as before with no more change than seems to be necessary. Additions and diversions in the honourable continuance of ever learning more about the Great War years, the before and the after being equally important in trying to understand the reasons why it all started and the social and political changes that fell on our forebears during that tumultuous era.

We will continue to remember all those who gave their lives during the conflict as well as those who survived and returned to spend the rest of their lives feeling guilty perhaps as the lucky ones who had ‘survived’ what their mates had suffered in either death or serious injury.

Ralph

The New Chairman - Ralph Lomas b.1948

My interest in war started as a young lad in the fifties with the emergence of comic book adventures, b/w war films, an introduction to Biggles' books by my big brother, and thereon all things military and daring do but plenty of sport as well.

In the late 1970’s a family friend told me of his father, who had served in WW1 with the 1st Essex Bn, and died in Flanders in January 1918. He recommended reading Lynn Macdonald's book 'Passchendaele'. I remember how the veteran's stories had gripped my imagination and there was an interest born to find out more about this Great War.

That same friend arranged a trip to Belgium in 1984 to visit Tyne Cot where his father was one of 12,000 remembered on the wall. This trip and cemetery visit made a lasting impression.

In 2004 I was introduced to the WFA Lancashire & Cheshire Branch by then Branch Chairman, John Richardson. One of my first speaker experiences happened to be Peter Simkins and this encouraged me to join the Association.

With the retirement of Stan Grosvenor in 2005 I was approached by the WFA for advice on publishing the "ST!" Reprints which have since sold out except for Vol. 3. The Executive Committee then asked me to provide a proposal to take over the Bulletin to 'modernise, manage and develop' the overall process of supplying members with regular high-quality publications. I was appointed and additionally agreed to act as editor after nobody else applied for the job.

My first edition (75) was in June 2006. I’m currently preparing the '111th' edition, my 37th, for publication in August.

In 1988, after 24 years at various Advertising/Marketing companies, I set up my own contract Publishing company, APP Publishing Consultants Ltd., to develop and supply self-funding publications and print management services in the Association/Institution and Local Authority sector. 1st July this year is my 30th year.

Looking Back: The position on the Western front in April/May 1918

Ludendorff’s desperate follow up offensives, to the stalled Operation Michael, of 21 March to 4 April, would continue during the summer months. On 11th April Haig issued his famous “Backs to the wall…” directive. There followed a period of further intense German offensive activity right through to the end of July.

Following Michael came Georgette or the Battle of the Lys which opened on 9 April and turned the German attention to the rail route through Hazebrouck and the approaches to the channel ports of Calais, Boulogne and Dunkirk. German success here could choke the British into defeat but this stalled as well. Closely followed by Blücher Yorck, on 27th May, 3rd Battle of the Aisne, aimed at forcing the French armies in the South to draw forces from the North. More was to follow as the German leadership hammered away, ultimately failing.

11th May Speaker is Greg Baugham

“The Myth of Fighter Development in WW1”

We welcome for the first time to Stockport Greg Baughem. Greg has been researching the history of British and French air forces for over forty years, with a focus on how air power evolved in both countries. Retirement provides the time to turn research into books, with the first three in a series published.

His talk "From Flying Dreadnought to Dogfighter - The Troubled Birth of the British Fighter" destroys many myths about WW1 fighter development. Part talk, part detective story, it explains how the importance of air superiority was understood long before the First World War began, explores how the influence of naval thinking delayed the development of dogfighters like the Camel and SE5a and tracks down the mysterious Fighting Experimental dreadnoughts that the RFC wanted to use instead. Based on the article of the same name in the spring 2016 edition of Air Britain's Aeromilitaria, in turn based on one of the themes in his book Blueprint for Victory.

Books published: Blueprint for Victory, The Rise of the Bomber, The RAF in the Battle of France and the Battle of Britain, The Fairey Battle -a Reappraisal of its RAF Career Articles in RAF Air Power Review, Air Britain's Aeromilitaria and The Aviation Historian.

100 Years Ago

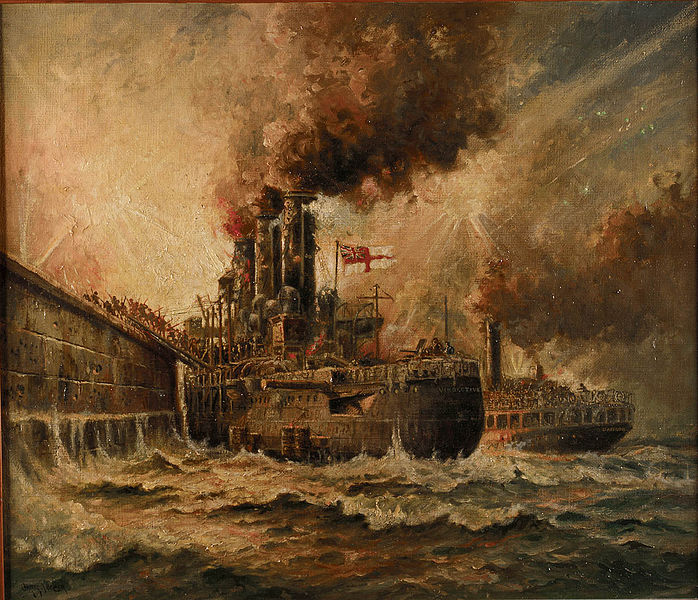

HMS Vindictive served with the Mediterranean Squadron from 1900, Captain Herbert Augustus Warren in command. She visited Larnaka in June 1902.

She was refitted in 1909–10 for service in the 3rd Division of the Home Fleet. In March 1912 she became a tender to the training establishment HMS Vernon. Obsolescent by the outbreak of First World War in August 1914, she was assigned to the 9th Cruiser Squadron and captured the German merchantmen Schlesien and Slawentzitz on 7 August and 8 September respectively.

In 1915 she was stationed on the southeast coast of South America. From 1916 to late 1917 she served in the White Sea.

Early in 1918 she was fitted out for the Zeebrugge Raid. Most of her guns were replaced by howitzers, flame-throwers and mortars. On 23 April 1918 she was in fierce action at Zeebrugge when she went alongside the mole, and her upper works were badly damaged by gunfire, her Captain, Alfred Carpenter was awarded a Victoria Cross for his actions during the raid. This event was famously painted by Charles de Lacy, the painting hangs in the Britannia Royal Naval College.

In addition to her usual complement, she embarked Royal Marine gunners to man the supplementary armament, and a larger raiding party. This comprised two of the three infantry companies of the 4th Battalion, Royal Marine Light Infantry, (their third company was embarked on the Iris), along with two "companies" of seamen raiders commanded by Lieutenant Commander Bryan Fullerton Adams and Lieutenant Arthur Chamberlain ("A" & "B" seamen Companies) respectively.

She was sunk as a blockship at Ostende during the Second Ostende Raid on 10 May 1918. HM Motor Launch 254 picked up 38 survivors of Vindictive's 55 crewmen. The ships Commander Alfred Godsal (photo right) perished on board. The wreck was raised on 16 August 1920 and subsequently broken up. The bow section has been preserved in Ostend harbour serving as a memorial. One of Vindictive's 7.5-inch howitzers was acquired and preserved by the Imperial War Museum.

The Zeebrugge and Ostende Raids, with their associated crop of VCs, had given the ship late celebrity and her name was perpetuated by renaming the

aircraft carrier HMS Cavendish, which was under construction, as Vindictive.

Terry

Last Month’s Talk

Jim Beach told the story of Vince Schürhoff. He was from a German family living in England at the outbreak of war. His father was a migrant who had moved to Birmingham. Vince had some education in Germany before coming to England

Vince was a twenty-six year-old corporal in the British army's Royal Engineers (Signal Service). In 1914 he had joined the army as an infantryman in the 3rd Birmingham City Battalion (Royal Warwickshire Regiment) and three years later, because he spoke fluent German, was seconded to signals intelligence work. In 1916 he had worked as an interpreter on the Somme and by 1918 was at Arras in his intelligence role which included interrogating German prisoners. Such men were rare and the army did not want to lose them as casualties. He could also speak French and Spanish.

At five in the morning on 21 March 1918, Vince Schürhoff woke to the thunderous sound of a bombardment. After many false alarms, the much-anticipated German offensive had begun

That day Vince was in command of what their inhabitants called an IToc (aye-tok) station and the army called a listening set post. Using metal probes and long loops of wire, Vince and his comrades could pick up German messages leaking from trench telephone lines or Morse buzzer messages sent through the earth (Likewise the Germans could tap our calls).

Vince had worked in several IToc stations and also as a prisoner interrogator, but in March 1918 he was in a deep dug-out near the devastated French village of Croisilles, south-east of Arras. This location happened to be at the northern end of the offensive that was meant to end the war in Germany's favour.

With Vince were two other linguists; Wilkie Roberts, a mariner who had worked on the German waterways, and Ernest Tucker, a Cambridge-educated librarian who, unsurprisingly, had a reputation for being a bit of a bookworm. His team also included two young signallers; William Corker from Durham, nicknamed Jelly Belly, and Cyril Haines from Hull.

The British were expecting the attack, so Vince's orders were to intercept German messages and pass them on to the local commander. If the Germans broke through, at the last safe moment they were to destroy their equipment and retreat.

After the initial bombardment, the German attack took a few hours to develop because their main thrust was further south. During this period Vince's team intercepted several German messages. Sprinting across open ground through the ongoing shelling, Vince delivered them to the nearest infantry battalion's headquarters. By two in the afternoon the situation seemed to have stabilised and Vince saw what he thought were British reinforcements approaching from the south. But when they got closer he realised they were German soldiers threatening to cut off their position. Vince decided it was time to go. He wrapped the listening amplifier in a blanket and ordered his men out from the safety of the dug-out.

All morning Vince's men had been anxious to withdraw, but when the time came the intensity of the bombardment caused one man to falter. Vince physically dragged him from the dug-out and, alternately running and crawling, they made their way to the rear. The infantry pulled out shortly afterwards.

Having reached the relative safety of the area behind Croisilles, Vince was alarmed when a very low-flying German aircraft strafed the road. In later years Vince's sleep would be haunted by the memory of the pilot looking down on him through his goggles.

Eventually the team trudged into the signallers' base camp a few miles back. Having lost contact with the station, Vince's captain had feared the worst. Much relieved to see them, he sat Vince down outside his tent, gave him a large beer and let him tell his story.

In subsequent weeks Vince returned to prisoner interrogation work. In May, with the German threat having subsided, he was summoned to corps headquarters where he was awarded the Military Medal for his actions on 21 March.

In his home city of Birmingham Vince's family were understandably very proud and ensured that the news featured in the local press. But they had a secondary motive beyond familial pride; they needed to demonstrate their loyalty to Britain.

Before the war Vince had been known by his real first-name, Fritz. His father was born in Germany but had become a British citizen after emigrating in the 1870s. During the First World War those of German birth came under suspicion. In early 1918, as the British army suffered reverses in France, the jingoistic press scapegoated these naturalised Germans, using the slogan "once a German, always a German".

So although their son had been decorated for fighting the Kaiser's army, the Schürhoff family - like the Royal Family a year earlier - decided to Anglicise their surname. They chose Shirley, apparently after the name of the Birmingham suburb.

But more suspicion was to come. In October 1918, with the British now in pursuit of the retreating German army, Vince and other interpreters with Germanic surnames were relieved of their intelligence duties and confined to the signals depot on the coast.

In January 1919 Vince returned to civilian life, although in the Second World War he put a uniform back on to serve in the Home Guard. We are fortunate that Vince also squirreled away the diaries that he had kept throughout the war. Fifty years later he transcribed them and wrote up some additional recollections. Copies are now deposited in the Imperial War Museum and the Military Intelligence Museum.

An interesting slant on what went on behind and under the lines Ed

Terry

NEXT Meeting 8th June: Speaker is Dr Michael LoCicero

‘A Moonlight Massacre’ - The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2 December 1917: The Forgotten Last Act of the Third Battle of Ypres.

The Third Battle of Ypres was officially terminated by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig with the opening of the Battle of Cambrai on 20 November 1917. Nevertheless, a comparatively unknown set-piece attack – the only large-scale night operation carried out on the Flanders front during the campaign – was launched twelve days later on 2 December. This volume is a necessary corrective to previously published campaign narratives of what has become popularly known as ‘Passchendaele’. It examines the course of events from the mid-November decision to sanction further offensive activity in the vicinity of Passchendaele village to the barren operational outcome that forced British GHQ to halt the attack within ten hours of Zero. A litany of unfortunate decisions and circumstances contributed to the profitless result. At the tactical level, a novel hybrid set-piece attack scheme was undermined by a fatal combination of snow-covered terrain and bright moonlight. At the operational level, the highly unsatisfactory local situation in the immediate aftermath of Third Ypres’ post-strategic phase (26 October-10 November) appeared to offer no other alternative to attacking from the confines of an extremely vulnerable salient. Perhaps the most tragic aspect of the affair occurred at the political and strategic level, where Haig’s earnest advocacy for resumption of the Flanders offensive in spring 1918 was maintained despite obvious signs that the initiative had now passed to the enemy and the crisis of the war was fast approaching.

Ralph Lomas